Lesson 8: Capstone 1 - Weather Forecasting App

Over the past couple of lessons, we have been getting familiar with the most common tools for the ClojureScript developer. While we have written a smattering of code, the focus has been on the project itself. This lesson will change course slightly and focus on writing a minimal app. This lesson will be a bit more difficult, and we will gloss over most of the detail of the code. The intent here is to present a picture of what a typical ClojureScript development workflow looks like without getting into the nitty-gritty details of the code. After learning the basic syntax and idioms of the language, we should be able to come back to this lesson with a much deeper understanding of what is going on.

In this lesson:

- Apply our knowledge of ClojureScript tools to create a new project

- Develop a ClojureScript application with a REPL-driven workflow

- Get a taste of the Reagent framework

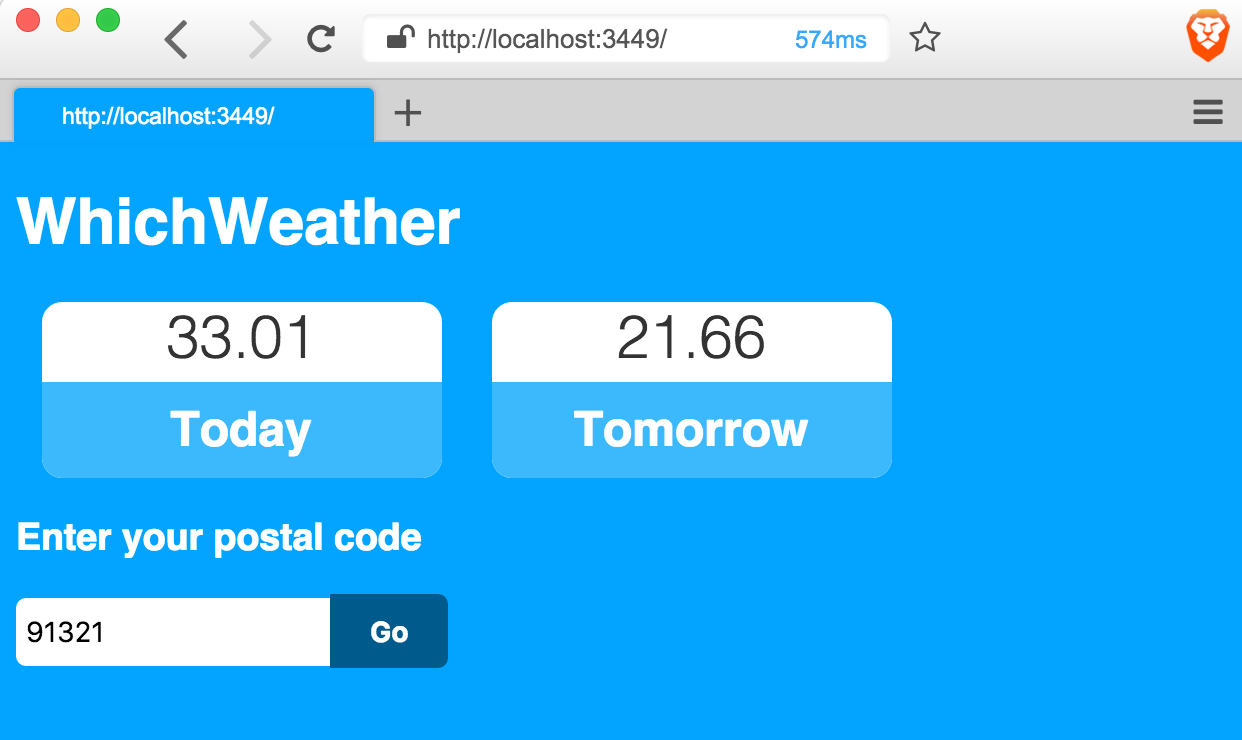

In this lesson, we’ll take the skills that we have learned over the past few lessons and put them to use developing a simple weather forecasting app that will accept user input, get data from a third-party API, and make use of React and the Reagent ClojureScript library for efficient rendering. This app will be simple enough to understand with only a minimal knowledge of ClojureScript yet will be representative enough to give us a clear picture of ClojureScript development. With that, let’s roll up our sleeves and start writing code!

A ClojureScript Single-Page App in Action

Creating an App With Reagent

We have seen how a typical ClojureScript application is laid out, and we have used clj-new to bootstrap a ClojureScript project. We have also explored the live reloading functionality and REPL that Figwheel provides to quickly iterate on small pieces of code. We will complete this high-level introduction to ClojureScript development by walking through a simple ClojureScript app. We will return to the application that we generated. We will see how quickly we can compose a ClojureScript application. The complete code for this lesson is available at the book’s GitHub repository, so feel free to simply pull the code and follow along. The goal here is not to learn the ins and outs of ClojureScript as a language but rather to get a feel for what production ClojureScript looks like.

Creating Reagent Components

Let’s begin by simplifying the core namespace so that it only contains a single Reagent component and renders it.

(ns ^:figwheel-hooks learn-cljs.weather ;; <1>

(:require

[goog.dom :as gdom]

[reagent.dom :as rdom]

[reagent.core :as r]))

(defn hello-world [] ;; <2>

[:div

[:h1 {:class "app-title"} "Hello, World"]])

(defn mount-app-element [] ;; <3>

(rdom/render [hello-world] (gdom/getElement "app")))

(mount-app-element)

(defn ^:after-load on-reload [] ;; <4>

(mount-app-element))

src/learn_cljs/weather.cljs

- Declare the namespace and load the Reagent framework

- Declare a simple Reagent component

- Render the Reagent component to the DOM

- Instruct Figwheel to re-mount the app whenever reloading code

Most ClojureScript user interfaces prioritize declarative components. That is, components describe how they should render rather than manipulating the DOM directly. The hello-world component in our application looks something like Clojurized HTML. In fact, the syntax of Reagent components is designed to emulate HTML using ClojureScript data structures. Like with other aspects of ClojureScript, Reagent encourages small components that can be combined from small structures into larger, more useful pieces.

This hello-world component is simply a function that returns a ClojureScript data structure. Imagining a JavaScript equivalent of this function is straightforward:

const helloWorld = () => {

return ["h1", {"class": "title"}, "Hello, World"];

};

Before moving on, we should remove the "test" directory from the :watch-dirs entry in our build configuration:

^{:watch-dirs ["src"] ;; Previously contained "test" as well

:css-dirs ["resources/public/css"]

:auto-testing true

}

{:main learn-cljs.weather}

dev.cljs.edn

We must remove the test directory because the scaffolded test contains a test case for a multiply function that we removed from the learn-cljs.weather namespace. If we did not remove this watch, Figwheel would not reload our code.

Quick Review

- The

hello-worldcomponent now has a class ofapp-title. Add an id attribute to the component as well and use your browser’s development tools to verify that the change worked.

Managing State in an Atom

Reagent runs this function and turns it into a structure that parallels the structure of the DOM. Any time that the function returns a different value, Reagent re-renders the component. However, in the case of this component, everything is static. For a component to be dynamic, it must render some data that could change. In Reagent, we keep all of the data that we use to render the app inside an atom, which is simply a container for data that might change. We have already seen an atom in use in the boilerplate code that we scaffolded in Lesson 5:

(defonce app-state (r/atom {:text "Hello world!"}))

Any Clojure data structure can be wrapped in an atom simply by wrapping it with (atom ...). Reagent components that make use of an atom will automatically re-render whenever the data inside the atom changes. This automatic re-rendering process is what enables us to write declarative components without worrying about tedious DOM manipulation.

For the weather forecasting app, we will keep the entire app state inside an atom wrapping a ClojureScript map: (atom {}). This will enable us to manage all of the data that we will need in a single location. This approach, when contrasted with the various approaches for managing data in some of the most popular JavaScript frameworks, is quite simple. The state for our weather forecast app will be quite simple, consisting of a title, a postal code that will be entered by the user, and several temperatures that we will retrieve from a remote API. We can create a skeleton of this app state in the cljs-weather.core namespace.

Initial application state

(defonce app-state (r/atom {:title "WhichWeather"

:postal-code ""

:temperatures {:today {:label "Today"

:value nil}

:tomorrow {:label "Tomorrow"

:value nil}}}))

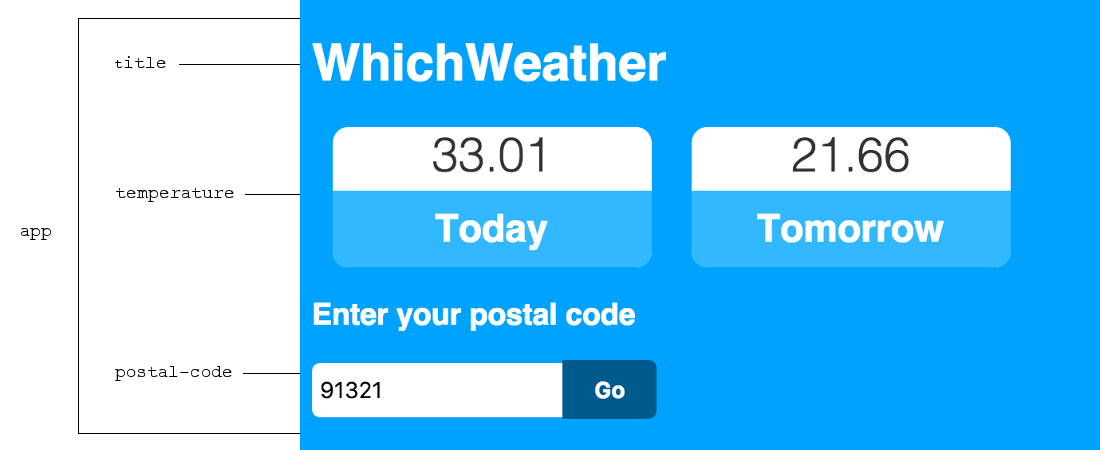

With the basic data structure in place we can identify and define the components that will make up our interface:

The Components of Our App

Reagent components

(defn title []

[:h1 (:title @app-state)])

(defn temperature [temp] ;; <1>

[:div {:class "temperature"}

[:div {:class "value"}

(:value temp)]

[:h2 (:label temp)]])

(defn postal-code []

[:div {:class "postal-code"}

[:h3 "Enter your postal code"]

[:input {:type "text"

:placeholder "Postal Code"

:value (:postal-code @app-state)}]

[:button "Go"]])

(defn app []

[:div {:class "app"}

[title] ;; <2>

[:div {:class "temperatures"}

(for [temp (vals (:temperatures @app-state))] ;; <3>

[temperature temp])]

[postal-code]])

(defn mount-app-element [] ;; <4>

(rdom/render [app] (gdom/getElement "app")))

- A Reagent component that expects

tempto be passed in - Nesting a component inside another component

- Render a

temperaturecomponent from each of the:temperaturesin the app state - Instruct Reagent to render

appinstead of thehello-worldcomponent

Responding to User Input

Now that we have an app running and rendering data, the next step is to let the user interact with the page. We will allow the user to input their postal code so that we can fetch weather data for their location. As we would in JavaScript, we attach an event handler to the input element. This handler will update the app state on every keystroke. The postal-code component already gets it value from the app state. The only step that we need to take is to attach the handler, and the input will stay synchronized.

[:input {:type "text"

:placeholder "Postal Code"

:value (:postal-code @app-state)

:on-change #(swap! app-state assoc :postal-code (-> % .-target .-value))}]

Handling Input with Reagent

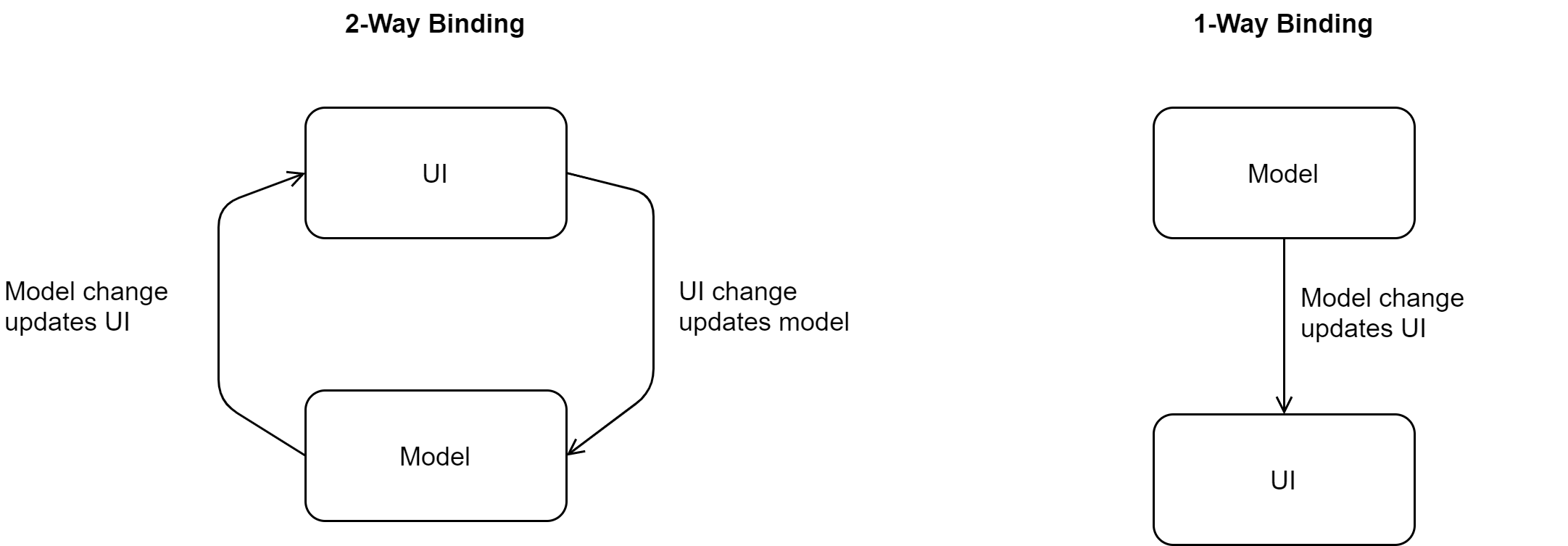

Note that this flow is different from the “2-way” data binding of JavaScript frameworks like Vue or Angular 1. For example, to achieve a similar effect in AngularJS, we would create a controller that manages some piece of state called postalCode and bind this state to an input. Internally, the framework ensures that whenever the state is updated, the input element is updated with the new value, and whenever the input value is changed by the user, the state is updated. Since the framework ensures that changes propagate in the direction of UI to model as well as model to UI, it is termed 2-way binding.

<div ng-app="whichWeather" ng-controller="inputCtrl"> <!--1-->

<input ng-model="postalCode"> <!--2-->

</div>

<script>

var app = angular.module('whichWeather', []); // <3>

app.controller('inputCtrl', function($scope) {

$scope.postalCode = ''; // <4>

});

</script>

Handling Input with AngularJS

- Provide indicators in our markup so that the framework knows which state to manage in the child elements.

- Create an input element and declare the state that it is bound to

- Create an app and controller to handle data and process interactions

- Initialize the state that will be bound to the input

While 2-way binding is convenient for very simple applications, it tends to have performance issues, and it can be more difficult for large applications with a lot of state, particularly derived data. The approach that we will be taking in most of the applications in this book is a little different and in fact, simpler. Instead of automatically syncing the application state and the UI in a bidirectional fashion, Reagent (and the underlying React framework) only updates the UI when the underlying state changes. Thus, we describe our components in terms of our data model, update that model when we receive input, and let the framework ensure that the UI reflects the new state.

Data Binding Strategies

With the one-way data binding, the model is considered the single source of truth, and all changes to the model are explicit. While this may seem like an inconvenience when compared to the more automatic 2-way binding, it is much easier to reason about and debug, and it enables much simpler logic in larger applications.

Quick Review

- Let’s assume that the postal code should always be a number. Change the component to use an HTML5

numberinput type. - Two way data binding actively updates a model whenever some input changes and also updates the view when the model changes. Explain how this process is different.

In order to verify that the input is actually updating the app state, we can use the REPL to inspect the current value of the app-state. Although the name of the app state variable is app-state, the UI components refer to it as @app-state. We will explore this operator in great detail later, but for our purposes now, we need to know that it will extract the current value of an atom. We can use this operator from the REPL just as we would from a UI component to view the current app state.

@learn-cljs.weather/app-state

;; {:title "WhichWeather", :postal-code "81235", :temperatures

;; {:today {:label "Today", :value nil}, :tomorrow {:label "Tomorrow", :value nil}}}

Calling an External API

The final piece of our weather forecast app is getting data from a remote API. While it is entirely possible to make an Ajax request using only the Google Closure libraries that are built in to ClojureScript, using an external library will greatly simplify the process. We simply need to add the cljs-ajax library to the :deps section of deps.edn and restart Figwheel. At that point, we can require the library in our namespace and start making requests.

{:deps {org.clojure/clojure {:mvn/version "1.10.0"}

org.clojure/clojurescript {:mvn/version "1.10.773"}

reagent {:mvn/version "0.10.0" }

cljs-ajax {:mvn/version "0.8.1"} ;; Added

}

;; ...

}

deps.edn

For the purpose of this application, we will use OpenWeatherMap’s forecast data API. Use of the API is free, but an account is required to obtain an API key.

With just 2 additional functions, we can enable communication with a remote API and hook the results into our user interface. While there is some unfamiliar ground in the code ahead, we can quickly understand the basics. First, we’ll consider how to process the results from the OpenWeatherMap API:

(defn handle-response [resp]

(let [today (get-in resp ["list" 0 "main" "temp"]) ;; <1>

tomorrow (get-in resp ["list" 8 "main" "temp"])]

(swap! app-state ;; <2>

update-in [:temperatures :today :value] (constantly today))

(swap! app-state

update-in [:temperatures :tomorrow :value] (constantly tomorrow))))

Handling the Response

- Extract data from the response

- Update the app state with the retrieved data

There are 2 pieces of data that we care about the data that the API provides - the current temperature and the forecasted temperature for 1 day in the future. handle-response takes care of extracting these pieces of data nested deep in the response and updates the values for today’s and tomorrow’s temperatures in the app state. Next, we’ll look at the code necessary to make the remote API request.

(defn get-forecast! []

(let [postal-code (:postal-code @app-state)] ;; <1>

(ajax/GET "http://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/forecast"

{:params {"q" postal-code

"appid" "API_KEY"

"units" "imperial"}

:handler handle-response}))) ;; <2>

Performing a Request

- Get the postal code from the

app-stateand supply it as an API request parameter - Handle the response with the

handle-responsefunction above

In the get-forecast! function, we extract the postal-code from our app state in order to request a localized forecast from the OpenWeatherMap API. Notice that we specify the handle-response function as the response handler, so when the API returns data, we will process it and update the app state accordingly. Finally, we want to create a UI component that the user can use to fetch data. In our case, we’ll use a simple button that will initiate the API request when clicked:

[:button {:on-click get-forecast!} "Go"]

We simply attach the get-forecast! function as an event handler on a button, and our work is done. The entire code from this lesson is printed below for reference. In order to correctly communicate with the API, please replace "API_KEY" in the listing below with the actual key from your OpenWeatherMap account.

(ns ^:figwheel-hooks learn-cljs.weather

(:require

[goog.dom :as gdom]

[reagent.dom :as rdom]

[reagent.core :as r]

[ajax.core :as ajax]))

(defonce app-state (r/atom {:title "WhichWeather" ;; <1>

:postal-code ""

:temperatures {:today {:label "Today"

:value nil}

:tomorrow {:label "Tomorrow"

:value nil}}}))

(def api-key "API_KEY")

(defn handle-response [resp] ;; <2>

(let [today (get-in resp ["list" 0 "main" "temp"])

tomorrow (get-in resp ["list" 8 "main" "temp"])]

(swap! app-state

update-in [:temperatures :today :value] (constantly today))

(swap! app-state

update-in [:temperatures :tomorrow :value] (constantly tomorrow))))

(defn get-forecast! [] ;; <3>

(let [postal-code (:postal-code @app-state)]

(ajax/GET "http://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/forecast"

{:params {"q" postal-code

"units" "imperial" ;; alternatively, use "metric"

"appid" api-key}

:handler handle-response})))

(defn title [] ;; <4>

[:h1 (:title @app-state)])

(defn temperature [temp]

[:div {:class "temperature"}

[:div {:class "value"}

(:value temp)]

[:h2 (:label temp)]])

(defn postal-code []

[:div {:class "postal-code"}

[:h3 "Enter your postal code"]

[:input {:type "text"

:placeholder "Postal Code"

:value (:postal-code @app-state)

:on-change #(swap! app-state assoc :postal-code (-> % .-target .-value))}]

[:button {:on-click get-forecast!} "Go"]])

(defn app []

[:div {:class "app"}

[title]

[:div {:class "temperatures"}

(for [temp (vals (:temperatures @app-state))]

[temperature temp])]

[postal-code]])

(defn mount-app-element [] ;; <5>

(rdom/render [app] (gdom/getElement "app")))

(mount-app-element)

(defn ^:after-load on-reload []

(mount-app-element))

Complete Weather Forecasting App

- Initialize the app state on load

- Handle API responses

- Perform API requests

- Define UI components

- Instruct Reagent to render the UI

While this app may not be a shining example of single-page application design, it is representative of the types of apps that we will be creating with ClojureScript. While its design is simple, this app demonstrates the major concerns that we are likely to face in any front-end app: component design, user interaction and communication with a data source. All said and done, we have created a complete weather forecast app in under 70 lines of code, including the pseudo-markup of the Reagent components.

You Try

- Modify the app to display a forecast for the next 4 hours

- Separate the “Go” button into its own Reagent component

Summary

In this lesson, we have surveyed a typical ClojureScript application. While the details of the application that we developed in this lesson will become clearer as we get a better handle on the syntax and idioms, we have a concrete example of how ClojureScript brings joy to the development process. We have seen:

- How a Reagent application defines UI components

- The difference between 2-way and 1-way data binding

- How to interact with an API