Lesson 11: Looping

In the last lesson, we looked at ClojureScript’s versions of we usually call branching control structure. However, we learned that things work a little bit different in ClojureScript compared to other languages that we may be used to - control structures are expressions rather than imperative controls. Now as we come to another fundamental topic - loops - we will learn that things are once again a bit different in ClojureScript.

In this lesson:

- Survey ClojureScript’s various looping structures

- Learn to think in terms of sequences

- Force evaluation of loops for side effects

In imperative languages, loops are used to repeat the same instructions multiple times, usually with some small variation each time that will eventually cause the loop to exit. The classic imperative loop is a while loop in which the computer simply executes the same instructions over and over until some condition is met:

let i = 0; // <1>

while (i < 10) { // <2>

console.log("Counting: " + i);

i++; // <3>

}

While Loop in JavaScript

- Initialize a variable that will be mutated

- Set the condition for continuing the loop

- Increment the value of

iafter every pass

Since ClojureScript emphasizes both immutability of data and expression-oriented programming - and loops are inherently both mutable and statement-oriented - one must wonder whether there is any place in ClojureScript for loops. The answer is both “yes” and “no” - there are several loop-like constructs, which we will look at momentarily, but upon closer inspection, they are abstractions for other concepts that do not involve explicit looping.

Manipulating Sequences with for

The first, and perhaps most common, expression that we will study in this lesson is for. Although it shares a name with a certain imperative loop, it is a different animal altogether. In contrast to the iterative for, ClojureScript’s for is centered around the idea of a sequence comprehension, in which we create a new sequence by transforming, and optionally filtering, an existing one. There are multiple ways to accomplish this task in ClojureScript, but for is certainly a concise and idiomatic option.

In its most basic form, for takes any number of sequences and a body, and it yields a new sequence by evaluating the body for every combination of sequence elements:

(for [elem1 sequence1 ;; <1>

elem2 sequence2] ;; <2>

expr) ;; <3>

for Dissected

- Bind each element from

sequence1in turn toelem1 - Do the same for

sequence2 - For every combination of elements from

sequence1andsequence2, evaluateexprwith the bindings,elem1andelem2

Using for With a Single Sequence

Although for supports an arbitrary number of sequences, in practice it is most commonly used with just one or two. The most common usage is - as we have already mentioned - as a sequence transformation. Say we have a list of numbers and we want to find the square of each of them. What we want is to somehow describe a process that yields a new list in which each element is the square of the corresponding element in the original list. Thankfully, this is even easier to express in code than in words:

(for [n (range 10)] ;; <1>

(* n n)) ;; <2>

;; (0 1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64 81)

Finding the Square of 0-9

- Yield a new sequence by taking the numbers 0-9

- Make each number in the new sequence the square of the original

By now we should see that when used with a single input sequence, for describes a whole-sequence transformation. When working with ClojureScript, we should try to think whether the problem before us could be represented as a sequence transformation. If so, for provides a no-nonsense solution. Let’s look at the same problem solved iteratively and with for. Imagine that we have a number of right triangles. We know the sides that are adjacent to the right angle, and we need to find the hypotenuse of each triangle. Fist, an iterative solution in JavaScript:

let sides = [[4.2, 6], [4, 4], [3, 4], [5.5, 3]]; // <1>

let lengths = []; // <2>

let i;

for (i = 0; i < sides.length; i++) { // <3>

lengths.push(

Math.sqrt(

Math.pow(sides[i][0], 2) +

Math.pow(sides[i][1], 2)

)

);

}

Get Hypotenuse Length Iteratively

- Model the triangle sides as a 2-dimensional array

- Declare an array to hold the resulting lengths

- Iterate over the elements in sides, pushing the calculated hypotenuse length into the

lengthsarray every time

This is pretty straightforward iterative code, but it is still lower-level than we would like in ClojureScript. With loops like this, it is easy to get indices mixed up (e.g. sides[i][0] versus sides[0][i]) or introduce off-by-1 errors. It is easy to see that this problem is just transforming one sequence into another, so we can easily use for:

(let [sides-list (list [4.2 6] [4 4] [3 4] [5.5 3])] ;; <1>

(for [sides sides-list] ;; <2>

(Math.sqrt (+ (Math.pow (first sides) 2) ;; <3>

(Math.pow (second sides) 2)))))

;; <4>

;; (7.323933369440222 5.656854249492381 5 6.264982043070834)

Get Hypotenuse Length With for

- Declare a list or pairs that each represent 2 sides of a right triangle

- Use a for expression to apply a transformation to every pair in the list

- Apply the Pythagorean Theorem to find the length of the hypotenuse

- The result is a sequence with the hypotenuse of each triangle

Quick Review:

- Given pairs of points as: [[x, y], [x, y]] coordinates, write a

forexpression that calculates the distance between the points. Hint: This is very similar to the previous example.

Using for With Multiple Sequences

Some of the power of for comes in its ability to combine elements from multiple sequences. When given multiple sequences, it will yield an element for every unique combination of single elements from each input sequence. This type of combination is called the Cartesian product and is an important concept in mathematical set theory. Imagine we are writing an e-commerce app, and for any given product, there are several variations: color, size, and style. We could use for to get all of the possible product combinations:

(let [colors [:magenta :chartreuse :taupe] ;; <1>

sizes [:sm :md :lg :xl]

styles [:budget :plain :fancy]]

(for [color colors ;; <2>

size sizes

style styles]

[color size style])) ;; <3>

;; ([:magenta :sm :plain] [:magenta :sm :regular] [:magenta :sm :fancy]

;; ... [:taupe :xl :plain] [:taupe :xl :regular] [:taupe :xl :fancy])

Generating Product Variations with for

- Declare 3 sequences

- Take every possible combination of 1 item from each collection

- Yield a vector of each color, size, and style combination

In this example, we did not do anything with the resulting product combinations other than pack them into a vector of [color size style], but we could have performed any sort of transformation we wanted. Consider that to accomplish the same task using an iterative loop would have required us to write loops nested 3 levels deep!

Loop modifiers: let, when, and while

So far, we have been using only the basic form of for in which we take every element from one or more sequences. While this works for many use cases, there are times that we want to filter the results (say, we don’t want to offer fancy products in the small size). Instead of filtering the list after for generates it, we can build the filtering logic directly into the for expression itself using the :when modifier. Again, there are times that we want to calculate some intermediate value before yielding a result. Instead of nesting a let expression inside body of the for, we can use the :let modifier. Finally, if we only want to take elements up to some cut-off point, we can use the :while modifier. To illustrate these modifiers, we will use a somewhat contrived example:

(for [n (range 100) ;; <1>

:let [square (* n n)] ;; <2>

:when (even? n) ;; <3>

:while (< n 20)] ;; <4>

(str "n is " n " and its square is " square)) ;; <5>

;; ("n is 0 and its square is 0"

;; "n is 2 and its square is 4"

;; "n is 4 and its square is 16"

;; ...

;; "n is 18 and its square is 324")

for Modifiers

- Take n from the range of 0-99

- Declare a binding for the symbol

squarefor each iteration as the square of n - Only include values for which n is even

- Only continue until n reaches 20

To use any of these modifiers, we can simply append it to the list of sequence expressions. None of these modifiers are difficult to understand, so we will simply outline each of them below briefly before moving on.

- :let creates any number of bindings within the body of the

for. It can use any of the symbols that are defined in theforexpression as well as any other vars in scope. The usage is identical to the regularletform. - :when determines for which inputs to emit a value. It is followed by a predicate expression, and it will emit a value if and only if the expression is truthy.

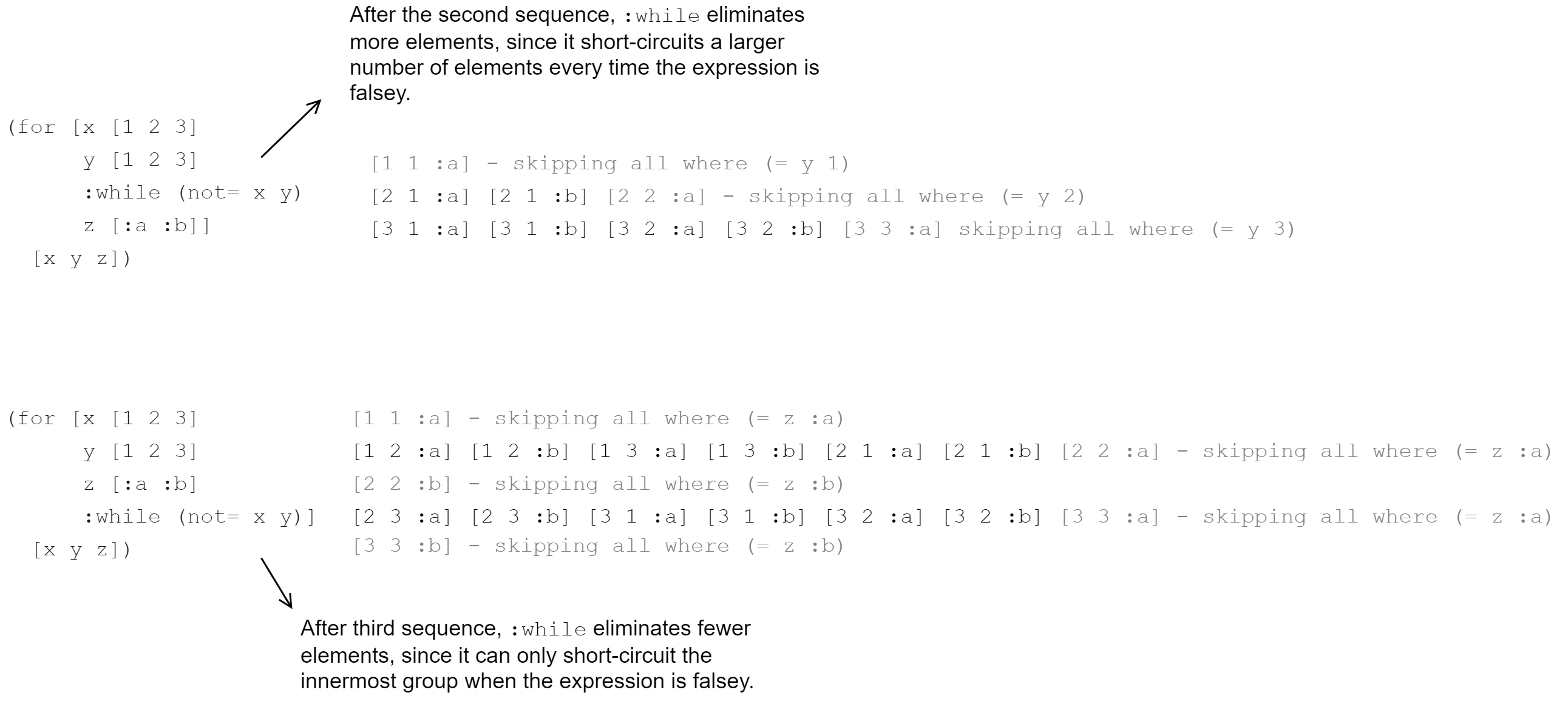

- :while is like

:when, but it short-circuits the most immediate “group” when used with multiple input sequences. That is, when placed after some sequence expression, it will skip the remaining elements in the sequence after which it is placed and continue with the combination that is formed by taking the next item in the previous sequence and the first item in the sequence after which it is placed. To illustrate this behavior, consider how the placement of the while clause affects the behavior of the following example:

Behavior of :while Modifier

Quick Review

- White a

forexpression that takes 2 values calledxandyboth from(range 50)and yields the pairs[x y]for all even values ofxand odd values ofywhen the product ofxandyis less than100. - Go back to the product variations example and use

:whento filter out all variations that are both:magentaand:fancy.

Performing Explicit Recursion with loop and recur

In the next lesson, we will look in more detail at recursive functions - that is, functions that call themselves. But as a preview, below is a simple recursive function that uses the Euclidean algorithm for calculating the greatest common denominator of two numbers.

(defn gcd [x y] ;; <1>

(if (= y 0)

x

(gcd y (mod x y)))) ;; <2>

;; #'cljs.user/gcd

(gcd 90 60) ;; <3>

;; 30

A Recursive Function

- Define a

gcdfunction using the Euclidean algorithm - The function calls itself as the last thing it does

- Test the function with inputs

90and60

The next loop-like construct that we will look at is the dynamic duo of loop and recur. We use loop/recur in cases where we want to use a recursive process but do not need a separate, named function for it. The general form that we use with loop is as follows:

(loop [name-1 init-value-1 ;; <1>

name-2 init-value-2]

body-exprs ;; <2>

(recur next-value-1 next-value-2)) ;; <3>

loop Dissected

- Pass in any number of bindings along with their value for the first pass of the loop

- Any number of body expressions

- Optionally recur to the beginning of the loop, supplying the values for each binding during the next iteration

This is the closest construct to an imperative loop that ClojureScript has to a traditional imperative loop. 1 Translating our gcd function from above into a loop/recur form is trivial:

(defn gcd-loop [a b]

(loop [x a ;; <1>

y b]

(if (= y 0)

x ;; <2>

(recur y (mod x y))))) ;; <3>

;; #'cljs.user/gcd-loop

(gcd-loop 90 60)

;; 30

Implementing gcd with loop

- Initialize the loop with the function’s inputs

- Return

xwhenyis0 - Recur in the case that

yis not0

As we see above, we can easily control when the loop exits and when it recurses by placing the call to recur inside one branch of a conditional and another value in the other branch. This gives us the same sort of granularity that we are probably used to with imperative loops, but with less boilerplate.

recur Nuances

loop is a very useful construct that lets us simplify many types of recursive functions. However, it cannot replace all recursive functions, only a particular class known as “tail recursive” functions. These particular functions are ones that call themselves as the very last thing they do (in the “tail” position) of the function. As we mentioned in the last lesson, every time a recursive function calls itself, it consumes a stack frame, and if it recurses too deeply, the JavaScript runtime will stop execution with an error. However, recursive processes written with loop and recur can recurse arbitrarily deeply because the ClojureScript compiler is able to optimize them into an imperative loop. For this reason, loop is also usually faster than functional recursion.

Because loop only works with tail recursion, we need to be careful that no evaluation is attempted after a recur. Thankfully, the ClojureScript compiler warns us if the recur is not in the tail position, and it will not compile the code until we move the recur. Below is an example of a proper call to recur along with an illegal one.

(loop [i 0

numbers []]

(if (= i 10)

numbers

(recur (inc i) (conj numbers i)))) ;; <1>

;; [0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]

(loop [i 7

fact 1]

(if (= i 1)

fact

(* i (recur (dec i) (* i fact))))) ;; <2>

;; ---- Could not Analyze <cljs form> line:5 column:22 ----

;;

;; Can't recur here at line 5 <cljs repl>

;;

;; 1 (loop [i 7

;; 2 fact 1]

;; 3 (if (= i 1)

;; 4 fact

;; 5 (* i (recur (dec i) (* i fact)))))

;; ^---

;;

;; ---- Analysis Error ----

;; nil

Legal and Illegal recur

- It is legal to recur when it is the last thing to be evaluated in a loop

- Cannot recur here because we need to multiply by

iafter recurring

So we see that not every recursive function can be translated into a loop, but if it can, there is a definite performance benefit. This has been a rather brief introduction to loop, but we will use it quite often over the course of this book, so we will have ample opportunity to get more familiar with it.

Looping for Side Effects

Having covered for for sequence comprehensions and loop/recur for explicit recursion. There is one remaining category of looping in ClojureScript: looping for side effects. Recall that a side effect is an effect that our program causes outside the pure calculations that it performs, such as adding and removing DOM nodes or sending data to a server-side API.

One of the difficulties with ClojureScript is that many of its sequence operations (including for) are lazy. That is, they do not produce results until called on to do so. Consider this for expression:

(for [i (range 100)]

(println i))

If you enter this into the REPL, it will print the numbers 0-99, just as we would expect. However, if we were to only request a few values from the sequence generated by the for, we would see a surprising result:

(take 3 ;; <1>

(for [i (range 100)]

(println i)))

;; 0 ;; <2>

;; 1

;; ...

;; 31

;; (nil nil nil) ;; <3>

(do (for [i (range 100)]

(println i))

(println "Done"))

;; Done

;; nil ;; <4>

Lazy Evaluation

- Only take 3 elements from the sequence given by the

forexpression printlngets called 32 times - not 100- Since

printlnreturnsnil, the result is a sequence filed withnil - No numbers are printed, since we never need the results of the

for

The for will only evaluate when the results are required to complete some other calculation. If some results are needed, then it will always evaluate at least as many elements as it needs to, but it may not evaluate the entire sequence2. This laziness is, as we will see in a later lesson, very useful for some things, but it can cause unexpected behavior when dealing with side effects, thus the need to force evaluation.

Evaluating an Existing Sequence With dorun

The first and simplest way to ensure that a sequence is fully evaluated (and thus all side effects that it may cause are run) is to wrap the sequence in a dorun. When just given a sequence, it will execute the code necessary to realize every value in succession, and it returns nil. For example, we could force the numbers to print in the example above simply by wrapping the for expression with dorun:

(do (dorun ;; <1>

(for [i (range 100)]

(println i)))

(println "Done"))

;; 0 ;; <2>

;; 1

;; ...

;; 99

;; Done

;; nil

Forcing Evaluation of a Lazy Sequence

- Wrap the

forindorun - All numbers are printed as expected

Looping for Effects With doseq

While dorun is often what we want if we have a sequence that performs side effects as each element is realized, we more often want to iterate over an existing sequence and perform a side effect for each element. In this case, we can use doseq. The syntax of doseq is identical to for (including the modifiers), but it evaluates immediately and returns nil instead of a sequence. If we think about sending a list of users to a back-end API, we certainly want to ensure that the code is evaluated when we expect it to, so we can use doseq, as in the example below:

(defn send-to-api [user] ;; <1>

(println "Sending to API:" user))

;; #'cljs.user/send-to-api

(let [users [{:name "Alice"}

{:name "Bob"}

{:name "Carlos"}]]

(doseq [user users] ;; <2>

(send-to-api user))

(println "Done!"))

;; Sending to API: {:name Alice} ;; <3>

;; Sending to API: {:name Bob}

;; Sending to API: {:name Carlos}

;; Done!

;; nil

- Stub the

send-to-apifunction - Iterate through the

userscollection - Side effects are performed immediately

Here we iterate through the users list and call send-to-api for each user. Since we do not care about the return value of that function, doseq is the perfect option here.

Quick Review

- What would happen if we had used

forin the previous example instead ofdoseq? - There is a function similar to

doruncalleddoall. Look it up online and explain when you might use one versus the other. - DOM manipulation is a side effect. What are some use cases for using

doseqin conjunction with the DOM?

Summary

We have now seen ClojureScript’s core looping features. While for and while loops are critical in many languages, we have learned that ClojureScript does not even have these concepts. Its looping constructs center around one of three things:

- Sequence operations (

for) - Recursion (

loop/recur) - Forcing evaluation of side effects (

doseq)

Even though we may at first find it difficult to solve problems without the traditional imperative loops, we will quickly discover that a “Clojure-esque” solution is often simpler. As we get more accustomed to thinking in terms of sequences and recursion, the ClojureScript way will become second nature.