Lesson 9: Using Variables and Values

ClojureScript takes what we think we know about variables and turns it on its head. Instead of thinking about variables that may be modified, we should start thinking about values that cannot be changed. While ClojureScript has the concept of a variable (called a var), we cannot usually change that value that a variable refers to. ClojureScript is careful to draw a distinction between a var and its value. Just like in JavaScript, variables may be redefined to refer to a different object; but unlike JavaScript, the object that the variable refers to cannot be changed. It is this core idea of programming with values that makes ClojureScript so interesting. In fact, values are at the core of every functional programming language, and we will find the the combination of immutable values and pure functions (which we will discuss in lesson 12 then again in Unit 4) enable a style of programming that is very easy to reason about.

In this lesson:

- Understand the difference between an immutable value and a mutable variable

- Learn the two primary ways of naming values -

defandlet - Explain the value or programming with values

Understanding Vars

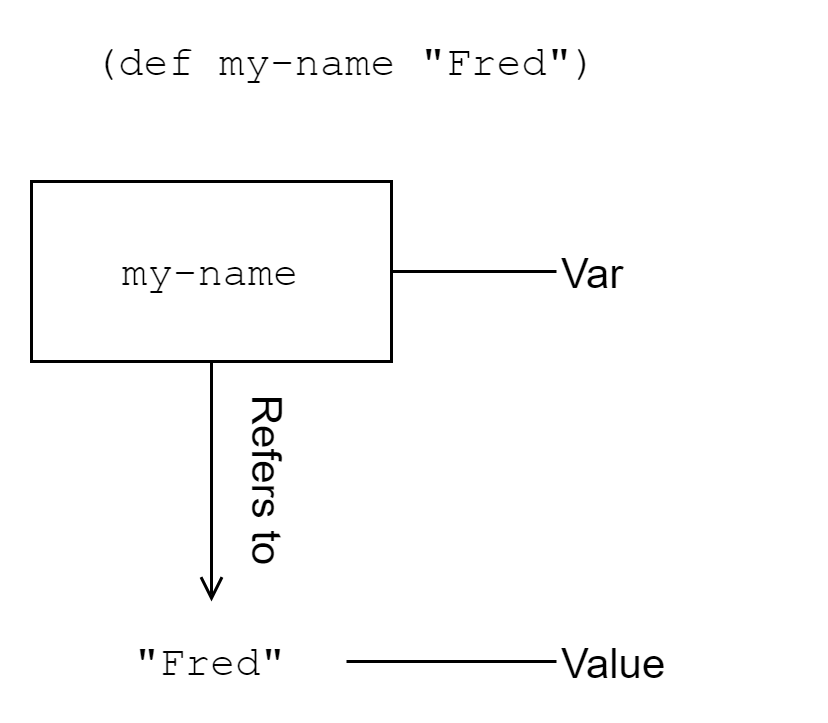

A var is very similar to a JavaScript variable. It is a mutable reference to some value. The fact that it is mutable means that we can have it refer to one value initially and later refer to someone else.

Imagine going to a party where every person is a stranger to everyone else. When you walk in the door, you are given a name tag on which to write your name. Chances are, the name that you write on your name tag will be the name that the other party-goers will use to address you. Now imagine that you swap name tags with another attendee who had a different name. You as a person will remain unchanged. Receiving a new name tag does not change your identity, only the name that others will use to refer to you. Additionally, people are now using the name from your original name tag to refer to someone else. Just because the name tag does not belong to you anymore does not mean that it is invalid.

Binding a Var to a Value

This fictional situation is an analogy to how vars and values work - the values are the people at the party, and the vars are the name tags. Just as names may be changed without affecting the people who bear them, vars may be changed without affecting the values that they name. The process of associating a var and a value is called binding the var to a value. Please feel free to follow along in the REPL.

(def my-name "Fred") ;; <1>

;; #'cljs.user/my-name

my-name

;; "Fred"

(defn mk-global [value]

(def i-am-global value))

;; #'cljs.user/mk-global

mk-global ;; <2>

;; #object[ ... ]

(mk-global [4 8 15 16 23 42])

;; #'cljs.user/i-am-global

i-am-global ;; <3>

;; [4 8 15 16 23 42]

(def ten 10)

;; #'cljs.user/ten

(def twenty (* ten 2)) ;; <4>

;; #'cljs.user/twenty

twenty

;; 20

ten ;; <5>

;; 10

Defining vars

- Binding the var,

my-nameto the value"Fred" defncreated a function and bound it to the var,mk-global- Even though the

i-am-globalvar was defined inside themk-globalfunction, it is global to thecljs.usernamespace - Since expressions evaluate to values,

twentygets bound to the result of(* ten 2), or20 - We verify that the value of ten was not changed when we multiplied it by 2

Symbols

In lesson 3, we looked very briefly at symbols, which are essentially names that refer to something else, usually a var. In the REPL session above, my-name, mk-global, i-am-global, ten, and twenty are all symbols. That is, they are names that refer to the var that we have bound. When ClojureScript is evaluating our program code and comes across a symbol, it will try to evaluate the symbol to whatever it refers to, and if it cannot resolve the symbol to any known value, it will display a warning.

(def x 7) ;; <1>

;; #'cljs.user/x

x ;; <2>

;; 7

'x ;; <3>

;; x

(defn doubler [x] (* 2 x)) ;; <4>

;; #'cljs.user/doubler

(doubler 3)

;; 6

y ;; <5>

;; WARNING: Use of undeclared Var cljs.user/y at line 1 <cljs repl>

;; nil

Symbols

- Use the symbol

xto refer to a var - The symbol evaluates to the thing it refers to

- A quote before the symbol causes ClojureScript to evaluate the symbol itself, not the thing it refers to

- Within the function, the symbol

xrefers to the function parameter, not the global var - Warning when trying to evaluate a symbol that does not refer to anything

You Try It

Almost everything in ClojureScript is a value, and a var can be bound to any value. With this knowledge, use def to create a var that refers to this function:

(fn [message]

(js/alert (.toUpperCase (str message "!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!"))))

Can you use the var that you created to call this function? E.g. (my-var "inconceivable")

You Already Know How to Use It

In JavaScript, we already work with immutable data on a daily basis. Strings and numbers in JavaScript are immutable - they are values that can not be changed. We can derive new values from them, but we (thankfully) can’t say that

1 = 2or"Unchangeable" += "... or not". It is perfectly natural for us to think about these sorts of values as immutable, but we have a more difficult time thinking about collections as immutable. More seasoned programmers who have encountered immutable data structures may tend to think of them as “bulky” or resource-intensive (and many implementations of them are indeed inefficient). Whether we are simply used to mutable collections from other languages or have a notion of immutable collections as being impractical, it takes a while to get into the habit of working with immutable collections However, once we get used to it, thinking of maps, vectors, et al. as values becomes as natural as thinking about strings and numbers in the same way.

Creating Local Bindings With let

While def creates a var that is visible to an entire namespace, we sometimes want to name and use values that are more temporary or focused in scope. ClojureScript uses let to create these local bindings. Like vars, let maps a name to some value, but they do not stick around after the contents of the let are evaluated. This can be useful for when we want to name things for convenience in the middle of a function without polluting the namespace with a bunch of unnecessary vars. The form of a let expression is as follows:

(let [bindings]

expr1

expr2

...

expr-n)

bindings are pairs of names and values, such as [a 20, b 10, c (+ a b)], and the entire let expression evaluates to the value of the last expression inside the body of the let. Since only the value of the last expression is considered, the other expressions are only used for side effects, such as printing to the console or doing DOM manipulation. Here is an example of how we might use let in a real application:

(defn parse-msg [msg-raw]

(let [msg-types {:c ::control

:e ::event

:x ::error}

msg (reader/read-string msg-raw)

type (:t msg)

data (:d msg)]

(println "Got data:" data)

[(get msg-types type) data]))

There are a couple of important things to notice here. First, the names that we created with the let - msg-types, msg, type, and data - are only defined for code inside the let and will be garbage collected when the let completes evaluation. Second, the names that we declare first are available in later bindings. For example, we defined msg as the result of evaluating the expression, (reader/read-string msg-raw), and then we defined type and data in terms of msg. This is perfectly normal and allows us to write much clearer and more concise code.

Quick Review

- What happens when

letcreates a binding with the same name as a var that is already defined? What will be the output of the following code?

(def name "Napoleon")

(let [name "Pedro"]

(println "Vote 4" name))

- Fill in the following function so that it tells you the name of your favorite dessert:

(let [desserts ["Apple Pie" "Ice Cream Sandwiches" "Chocolates" "Berry Buckle"]

favorite-index 1

favorite-dessert (get desserts favorite-index)]

(println "All desserts are great, but I like" favorite-dessert "the best"))

Destructuring Bindings

The let form allows us to do more than bind a single name at a time. We can use it to assign names to elements in a list or vector as well as entries in a map. In the simplest case, we can declare a vector of names on the left-hand side of the binding and a sequence on the right-hand side. The nth name in the vector will be bound to the nth element in the sequence on the right (or nil if no such element exists):

(let [[id name rank extra] [420 "Pepper" "Sgt."]]

(println "Hello," rank name "- you have ID =" id "and extra =" extra))

;; Hello, Sgt. Pepper - you have ID = 420 and extra = nil

If we are not interested in assigning a name of a particular element, we can use an _ as its name, as in the following example:

(let [[_ name rank] [420 "Pepper" "Sgt."]]

(println "Hello," rank name))

;; Hello, Sgt. Pepper

Another common case is assigning some trailing portion of a sequence to a name. This can be done by inserting a & other at then end of the binding:

(let [[eat-now & eat-later] ["nachos" "salad" "apples" "yogurt"]]

(println "Please pass the" eat-now)

(println "I'm saving these for later:" eat-later))

;; Please pass the nachos

;; I'm saving these for later: (salad apples yogurt)

In addition to destructuring lists and vectors, we can also destructure maps by providing a map on the left-hand side of the binding whose keys are the names to which the properties should be bound and whose values are the keys in the map on the right-hand side to bind:

(let [{x :x

y :y} {:x 534 :y 497 :z -73}]

(println "Inspecting coordinates:" x "," y))

;; Inspecting coordinates: 534 , 497

However, since we often work with maps of keywords, there is a more succinct way to bind specific values from a map to names that are similar to their key:

(let [{:keys [x y z]} {:x 534 :y 497 :z -73}]

(println "x = " x "| y = " y "| z = " z))

;; x = 534 | y = 497 | z = -73

For maps with string keys there is a similar syntax that uses :strs instead

of :keys in the binding.

Finally, when destructuring maps, we may provide default values using :or inside the binding form followed by a map of name to default value:

(let [{:keys [fname lname profession]

:or {profession "professional"}} {:fname "Sasha" :lname "Simonova"}]

(println fname lname "is a" profession))

;; Sasha Simonova is a professional

There are more variations to ClojureScript’s destructuring forms1, but we have covered the most common ones that we will use for the rest of this book.

You Try It

- What happens when you use the

& otherform when there are no more elements in a list/vector?

(let [[one two & the-rest] [1 2]]

the-rest)

Summary

We have now gone over the two primary means of naming things in ClojureScript def for namespace-level bindings and let for local bindings - so we are ready to tackle one of “the only two hard problems in computer science”2. Combining this knowledge with what we will learn in the next few lessons, we will be able to start writing some interesting applications. We can now:

- Explain what a var is and how it is referred to by a symbol

- Define global bindings using

def - Define local bindings using

let - Destructure sequences and maps

The official Destructuring in Clojure guide is an excellent reference ↩︎

Did you catch the reference to Phil Karlton’s famous quote, “There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.” ↩︎