Lesson 16: Grokking Collections

So far, we have been working with simple data types - strings, numbers, keywords, and the like. We saw a few collections when we took our survey of ClojureScript’s syntax, but we glossed over exactly what they are and how to use them in real applications. As we might imagine, writing programs without any way to represent data that belongs together would be cumbersome at best. JavaScript has arrays for representing lists of things and objects for representing associative data - that is, data in which values are referred to by a specific string key, such as the title and content of a blog post. We are probably already familiar how these types of collections work from JavaScript or another language.

In this lesson:

- Using lists for managing ordered data

- Using maps for looking up values by a key

- Using sets for keeping data unique

Example: Contact Book

It should come as no surprise that collections are a core feature of ClojureScript - much more, in fact, than in most other languages. We deal with collections every day. Take the example of a contact book where we store details for friends and acquaintances. The contact book itself is a collection of contact details, and each contact itself is a collection of personal information.

A contact book is a real-world collection

In JavaScript, we might model the contact book itself as a list and each individual contact as an object with the properties, name, address, etc. It would probably look something like the following:

const contactBook = [ // <1>

{

name: "Phillip Jordan",

address: "523 Sunny Hills Cir.",

city: "Springfield",

email: "phil.j@hotmail.com"

},

{ // <2>

name: "Clara Michaels",

address: "4473 Point of the Pines",

city: "Colorado Springs",

email: null

}

];

Modeling a Contact Book in JavaScript

- Outer structure is an array for organizing a list of contacts

- Inner structure is an object for describing a contact by a specific set of properties

While we can effectively write programs using the arrays and objects that JavaScript provides, ClojureScript gives us more focused tools, and - more importantly - abstractions. In JavaScript, we can sort or filter a list, and we can lookup a property on an object. They are different data types that have essentially different behaviors. In ClojureScript, there are multiple collection types that all conform to a specific collection protocol. For those familiar with the concept of an interface, all ClojureScript collections conform to a common interface. That means that any code that is designed to work with a collection can work with any collection, whether that is a vector, set, list, or map. We can then choose the specific collection type that we want to use based on its performance characteristics and have confidence that we can use the same familiar functions to operate on it. Not only that, but we can implement the collection protocol in our own code, and ClojureScript can operate on our own objects as if they were built into the language itself.

Defining Collections and Sequences

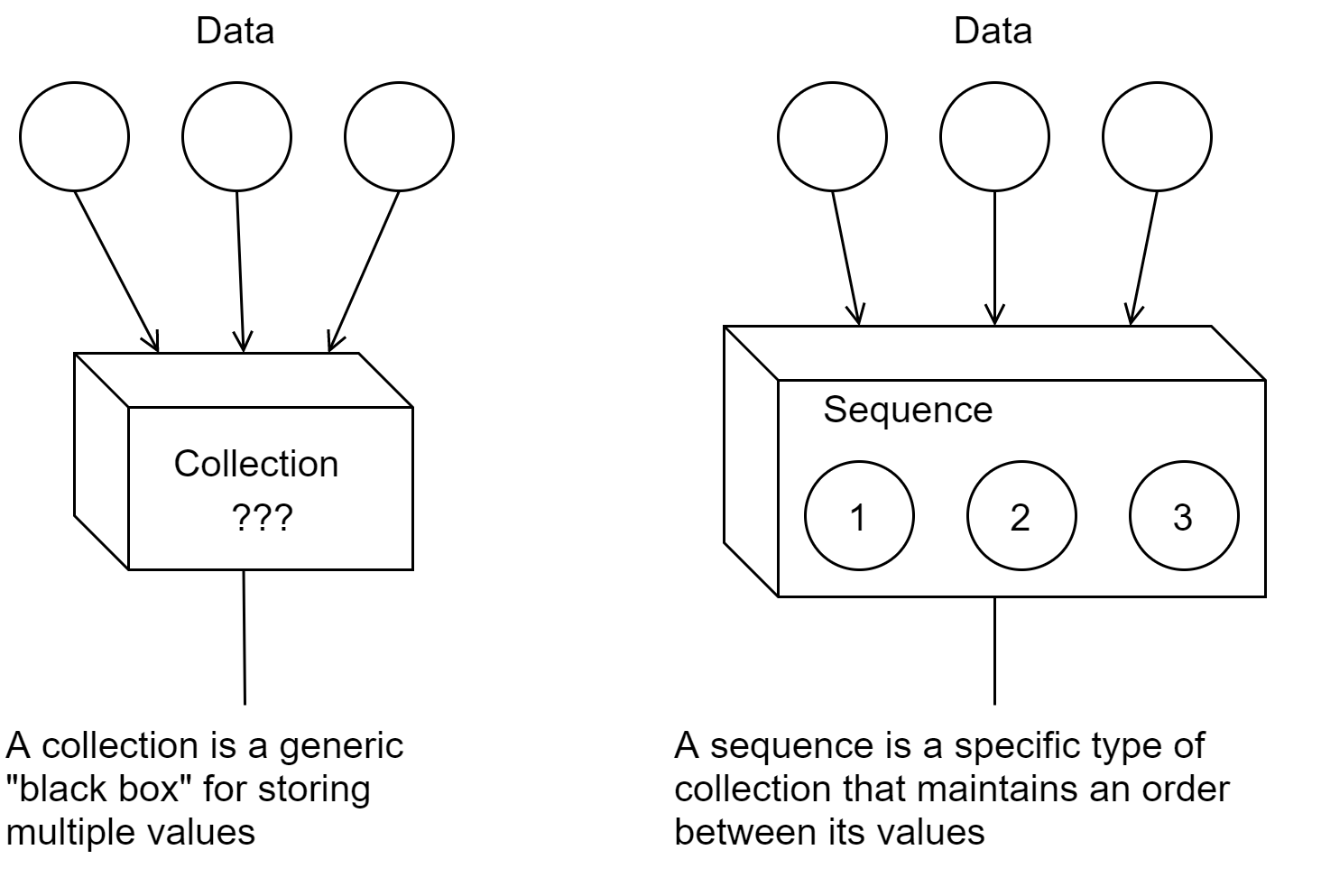

Let’s take a brief step back to define what a collection is and to take a look at a closely related concept, the sequence. In ClojureScript, a collection is simply any data type that holds more than one thing. It is the opposite of a scalar, which represents only a single thing. Another way to think of a collection is as a container for other data. A sequence, on the other hand, is a linear collection that has a beginning and an end. All sequences are collections (because they are containers), but not all collections are sequences.

Collections and Sequences

In order for ClojureScript to treat something as a collection, it only needs to be able to add something to it, and it does this by using the oddly named conj function (short for “conjoin”). How that something is added to the collection depends on the type of collection. For instance, items are added to the beginning of a list but to the end of a vector, and adding an item to a set only grows the set if the item does not already exist. We can see an example of the behavior of conj on different collections in the REPL.

cljs.user=> (conj '(:lions :tigers) :bears) ;; <1>

(:bears :lions :tigers)

cljs.user=> (conj [:lions :tigers] :bears) ;; <2>

[:lions :tigers :bears]

cljs.user=> (conj #{:lions :tigers} :bears) ;; <3>

#{:lions :tigers :bears}

cljs.user=> (conj #{:lions :tigers} :tigers) ;; <4>

#{:lions :tigers}

Using conj with different collections

conjadds to the beginning of a list- …or the end of a vector

- A set has no order, so the new element is simply added to it

- Adding an element that is already in a set has no effect

Quick Review: Collections

- What is the only operation that we can be sure that every collection will support?

- Which collection type should we use to efficiently add to the beginning with

conj?

Sequences

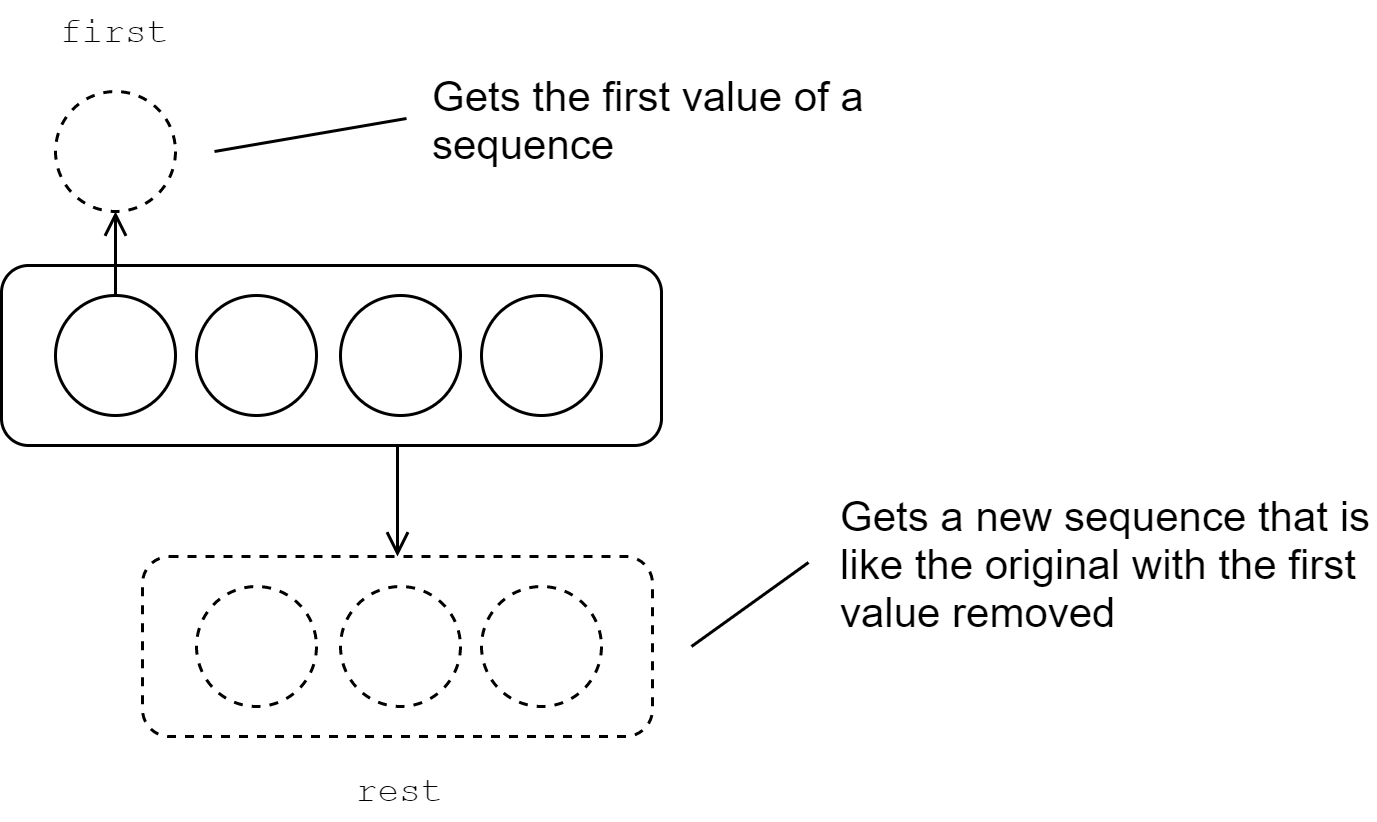

Sequences are a type of ClojureScript collection in which the elements exist in some linear fashion. Whereas collections need only support adding an element with conj, sequences must support 2 additional operations: first and rest. first should return the first item in the sequence, and rest should return another sequence with everything else. In the case that we have a singleton sequence - that is, a sequence with only one element - rest will evaluate to an empty sequence.

First and Rest of a Sequence

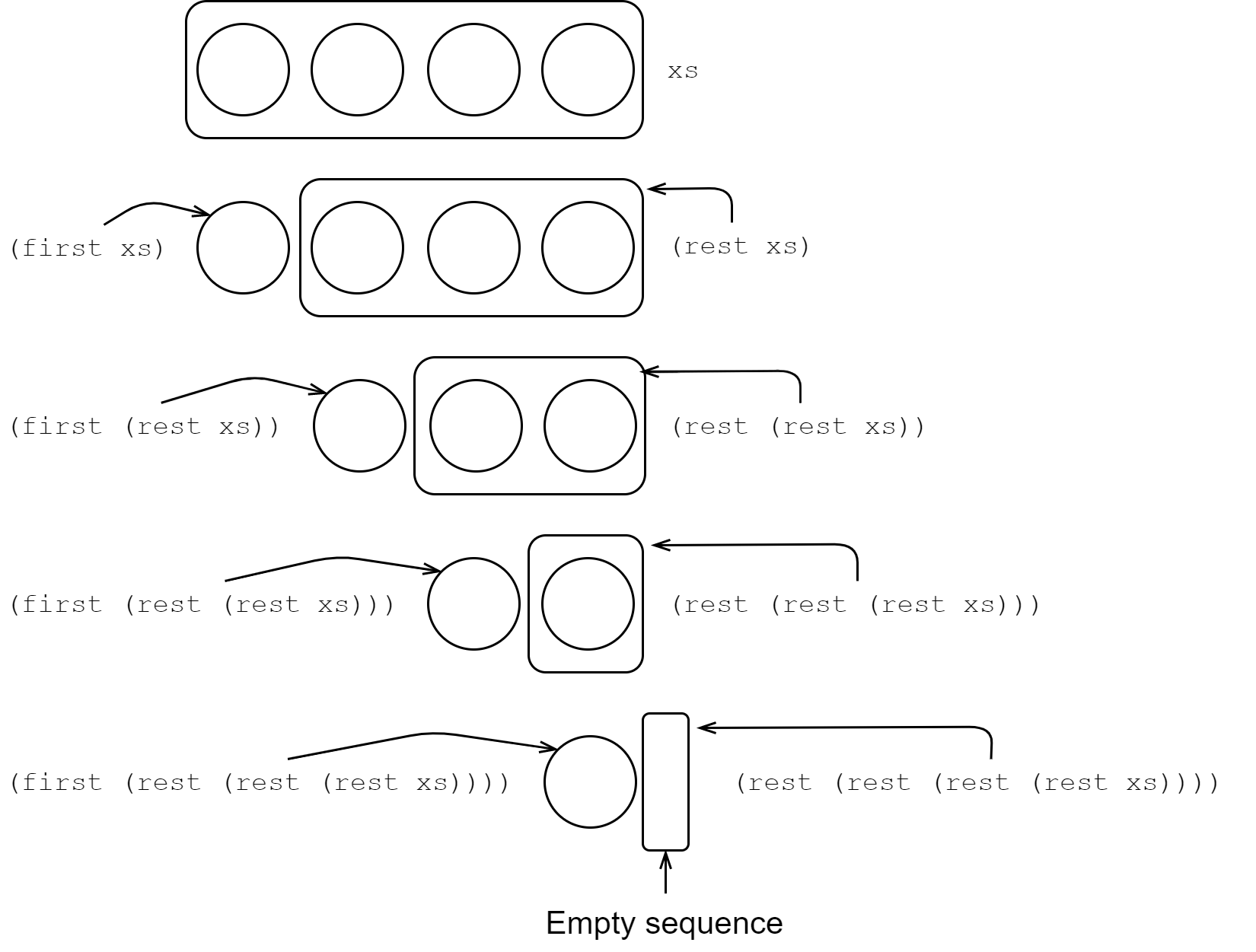

This sequence abstraction seems quite intuitive - as long as we can get the first bit of something an we can get another sequence with the remaining bits, we can traverse the entire sequence, taking the first bit off each time until nothing is left. Since the rest of a sequence is another sequence, we can take the first element of it until we finally get to the end. Keeping this in mind, we can create a function that performs some sort of aggregation over a sequence by repeatedly looping with the rest of a sequence until the sequence is empty. For example, to add all the numbers in a sequence, we could write the following function:

(defn add-all [xs]

(loop [sum 0 ;; <1>

nums xs]

(if (empty? nums) ;; <2>

sum

(recur (+ sum (first nums))

(rest nums))))) ;; <3>

Traversing a Sequence

- Initialize the loop with a sum of

0and all of the numbers that were given - When no numbers remain, return the sum that has been accumulated

- When there are still numbers left in the sequence, loop again with the old sum plus the first number in the sequence as the new sum and the

restof the numbers as the newnums

A visual will help us better understand what is going on here:

Traversing a Sequence

This process of repeatedly dividing a sequence between its first and rest illustrates a core concept in ClojureScript - sequence traversal. Thankfully, there is a rich library of functions that work with sequences, so we seldom have to write such tedious code as in the example above!

Extra Credit

- Look up the

reducefunction online. How could the add-all function be simplified usingreduce?

Quick Review: Sequences

- In general, how would you get the nth element of a sequence using only the

firstandrestfunction? - What is the

firstof an empty list? - What is the

restof an empty list?

It’s all about abstraction

Several JavaScript libraries - most notably lodash and Ramda - have similar functions that can get the first element and the rest of the elements from an array. The key difference between these libraries’ sequence functions and ClojureScript’s sequences is that sequences are an abstraction that are not intrinsically tied to any data type. If it looks like a sequence, then to ClojureScript, it is one. After getting used to programming to abstractions, JavaScript’s data types start to feel a bit rigid like, well, concrete.

Using Lists for Sequential Data

Lists are one of the simplest data types in ClojureScript. They are sequences that can hold other objects of any type that can efficiently be accessed starting at the beginning and progressing linearly. Lists are most often used in two cases: first, when we have a collection of data that will always be accessed from beginning to end, and second, when we want to treat some data as a stack where the last item added is the first one to retrieve. Lists, however, are not efficient for random access (i.e. getting the nth element in the sequence).

There are two ways to create a list in ClojureScript. The first is with the list function, and the second is using the literal syntax, '(). As collections, lists support adding elements with conj; and as sequences, they support first and rest.

cljs.user=> (list 4 8 15 16 23 42) ;; <1>

(4 8 15 16 23 42)

cljs.user=> '(4 8 15 16 23 42) ;; <2>

(4 8 15 16 23 42)

cljs.user=> (conj '(:west :north :north) :south) ;; <3>

(:south :west :north :north)

cljs.user=> (first '("Tom" "Dick" "Harry")) ;; <4>

"Tom"

cljs.user=> (rest '("Tom" "Dick" "Harry"))

("Dick" "Harry")

Working with lists

- Creating a list with the

listfunction - Creating a list with the literal syntax

- Prepending to a list with

conj - Treating a list as a sequence with

firstandrest

Using Vectors for Indexed Data

While lists are useful in some applications, vectors are much more widely used in practice. Think of vectors as the (immutable) ClojureScript counterpart of JavaScript’s array. They are a very versatile collection that can be traversed sequentially like a list or accessed by 0-based index. Unlike a list, conj adds elements to the end of a vector. For collections where we may want to get a specific element or extract a specific slice, a vector is usually the best choice.

cljs.user=> (conj ["Moe" "Larry"] "Curly") ;; <1>

["Moe" "Larry" "Curly"]

cljs.user=> (first ["Athos" "Porthos" "Aramis"])

"Athos"

cljs.user=> (rest ["Athos" "Porthos" "Aramis"]) ;; <2>

("Porthos" "Aramis")

cljs.user=> (nth ["Athos" "Porthos" "Aramis"] 1) ;; <3>

"Porthos"

cljs.user=> (["Athos" "Porthos" "Aramis"] 1) ;; <4>

"Porthos"

Working with vectors

conjadds to the end of a vectorrestalways returns a sequencenthlooks up a specific element by index- Vectors themselves are functions that can look up an element when given an index as an argument

We discovered a couple of interesting properties of vectors and sequences in the REPL session above. First, we see that when we applied the rest function to a vector, we did not get a vector back. Instead, what we got looked like a list but is in fact a generic sequence that acts much like a list. Since vectors are optimized for indexed access, ClojureScript performs some coercion whenever we use them as sequences. While this makes little difference most of the time, it is good to be aware of. Second, we see that in ClojureScript, vectors are functions that expect as their argument the index of an element to look up. That is why we could evaluate, (["Athos" "Porthos" "Aramis"] 1). Interestingly, almost everything in ClojureScript can be used as a function - vectors, maps, keywords, and symbols can all be used as functions (although if we do not give them the arguments that they require, we may get unexpected results).

We will be working with vectors a great deal, since their performance characteristics are appropriate in many real-world scenarios.

Using Maps for Associative Data

Maps are an incredibly useful collection that allow us to map keys to arbitrary values. They are the ClojureScript analog of JavaScript’s object, but they are much simpler. Whereas JavaScript objects can have functions attached to them with complex rules (and some might say dark magic) surrounding what this refers to, maps are simply data. There is nothing preventing the use of a function as a value in the map, but that does not create any binding between the function and the map.

We can think of a map as a post office. Anyone who has a mailbox is assigned a specific number that they can use to find their mail. When the post office receives mail for a specific customer, they put that mail in the box that is associated with that customer. Essentially, the post office maintains an association between a box number and the mail belonging to a single customer. Likewise, maps maintain an association between some identifying key and some arbitrary value.

Maps can be created either with the literal syntax, {}, or with the hash-map

function.

cljs.user=> {:type "talk" ;; <1>

:title "Simple Made Easy"

:author "Rick Hickey"}

{:type "talk", :title "Simple Made Easy", :author "Rick Hickey"}

cljs.user=> (hash-map :foo "bar", :baz "quux") ;; <2>

{:baz "quux", :foo "bar"}

Creating Maps

- The common way to create a map is to alternate keys and values inside curly braces

- Maps can also be created with the

hash-mapfunction, which takes alternating keys and values

When using maps as a collection with conj or as a sequence with first and rest, the behavior may not be intuitive. ClojureScript allows us to treat a map as a sequence of [key, value] pairs, so when we want to add a map entry with conj, we append it as a vector containing a key and a value.

cljs.user=> (conj {:x 10 :y 12} [:z 7])

{:x 10, :y 12, :z 7}

Similarly, if we take the first of a map, we will get some map entry as a [key, value] pair, and if we take the rest, we will get a sequence of such pairs. Knowing about this behavior will help us in the next lesson when we discuss the common functions used to operate on sequences.

cljs.user=> (first {:x 10, :y 12, :z 7})

[:x 10]

cljs.user=> (rest {:x 10, :y 12, :z 7})

([:y 12] [:z 7])

One other advantage of ClojureScript maps over JavaScript objects is that any value may be used as the key - not just strings. For instance, if we were creating a Battleship-like game, we could use a vector of grid coordinates as keys.

cljs.user=> {[:b 3] :miss, [:a 7] :hit}

{[:b 3] :miss, [:a 7] :hit}

While we can use any value as a key, keywords are most commonly used because of their convenient syntax and because they also act as functions that can look up the map entry associated with themselves in a map. This is an extremely common idiom in ClojureScript and one that will be used extensively throughout this book. Additionally, maps may also be used as functions (surprise!) that can look up the value associated with the key given as the argument.

cljs.user=> (def fido {:breed "Boxer" :color "brown" :hungry? true})

#'cljs.user/fido

cljs.user=> (get fido :breed)

"Boxer"

cljs.user=> (:color fido)

"brown"

cljs.user=> (fido :hungry?)

true

We have seen that there are quite a few usage patterns for dealing with maps. This is by no means a comprehensive reference, and we will continue to see more ways to work with maps in later lessons.

You Try It

- What happens when you try to

conjan element onto a map when that map already has a value for the key of the new element, e.g.(conj {:flavor "Mint"} [:flavor "Chocolate"])? - As we just saw, ClojureScript treats a map as a collection of

[key value]pairs. Knowing this, how might we add an entry to the following map such that we set a:priceof12.99?

(conj {:title "Kneuter Valve", :part-num 5523} ...)

Using Sets for Unique Data

A set in ClojureScript resembles a mathematical set, which can contain any number of elements, but they must be unique. Sets are often used for de-duplicating data in some other collection or for checking whether a piece of data is contained in the set.

cljs.user=> (def badges

#{:quick-study :night-owl :neat-freak}) ;; <1>

#'cljs.user/badges

cljs.user=> (contains? badges :night-owl) ;; <2>

true

cljs.user=> (conj badges :quick-study) ;; <3>

#{:quick-study :neat-freak :night-owl}

cljs.user=> (conj badges :clojurian) ;; <4>

#{:quick-study :neat-freak :night-owl :clojurian}

cljs.user=> (first badges) ;; <5>

:quick-study

- Creating a set using the literal syntax,

#{ ... } contains?is often used with sets and checks for membershipconjis a no-op if the element is already a member of the setconjadds a new member if it is unique- We can treat a set as a sequence, although the order of elements is arbitrary

While sets are not used as often as vectors and maps, they are incredibly useful when dealing with unique values.

Quick Review

- Which collection should be used to represent each of the following: a product on an e-commerce site, a news feed, tags attached to a blog post?

- Using the Clojure(Script) documentation, find:

- Additional functions that can be used with maps

- Additional functions that can be used with sets

- Explain in your own words the difference between a collection and a sequence.

Summary

This was a long lesson, but a crucial one in our understanding of ClojureScript. One of the key features of the language is its rich collection library, but in order to wield this library effectively, we must first have a grasp on the collections available to us. We have learned:

- How the collection library is based around two abstract types - the collection and the sequence

- How sequence functions are built on top of the

firstandrestfunctions - What data structures are built into ClojureScript and how they are used

Over the next few lessons, we will apply the collection library to some common UI programming problems, culminating in a contact book application.