Lesson 17: Discovering Sequence Operations

Programming is all about abstractions. The entire field of software engineering is devoted to making programs and systems that are better for human beings to reason about and maintain. The key to making clear and accurate systems is found in the concept of abstraction, which is identifying patterns that recur often and generalizing them to something that is more widely applicable. We humans are quite adept at abstracting concepts. In fact, it is one of the first skills that we learn in childhood. Imagine a toddler who calls every fruit that they see, “apple”, because they are familiar with an apple and have identified a number of similarities between it and other fruits. Eventually, this child will learn that there is a whole class of distinct but similar objects called “fruit”, each of which has its own unique properties yet shares many other properties with every other thing that we call fruit. The idea of abstraction in programming is very similar: we see a number of different constructs that appear similar in many ways, yet each of which are distinct from the rest, and we must determine how to appropriately generalize the properties that each construct shares in common.

In this lesson:

- Apply a transformation to every element in a sequence

- Efficiently convert between sequence types

- Filter sequences to only specific elements

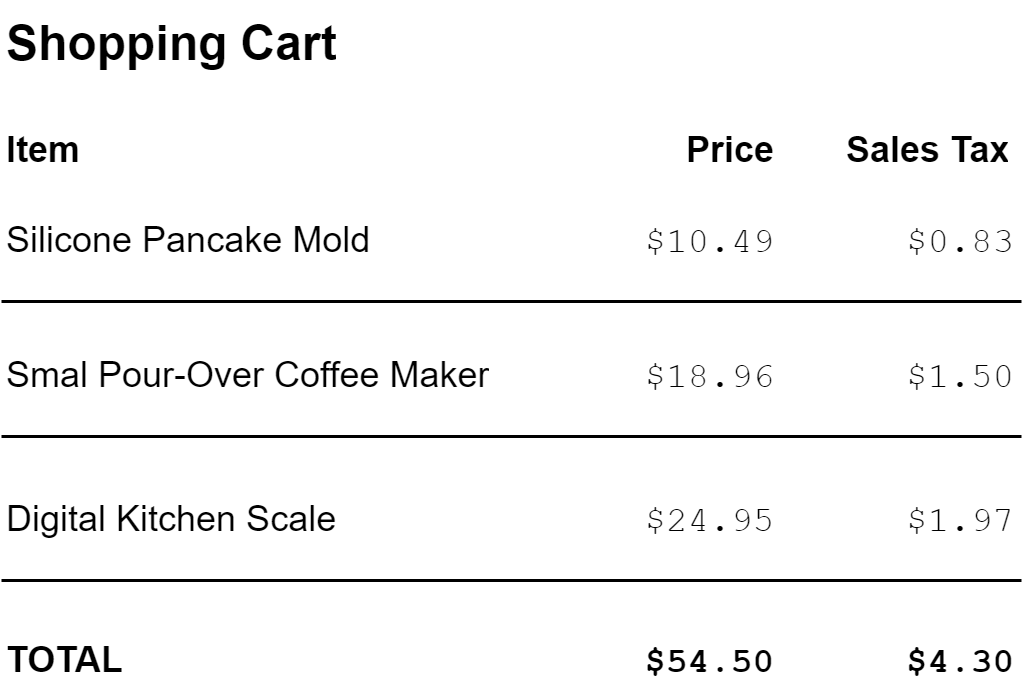

Example: Calculating Sales Tax

Imagine that we are writing an e-commerce shopping cart app. One of the requirements is that we display the sales tax for each item in the cart as well as a summary section with the total price and the total sales tax. We will learn to apply a couple of ClojureScript’s sequence operations to solve this problem.

The Sequence Abstraction

As we have seen in the previous lesson, ClojureScript has identified collections as an important general abstraction. The collection abstraction had the single operation, conj, for “adding” an item into the collection. The important point to remember is that each specific collection type defines what it means for an item to be added to it, and adding to a list, a vector, a set, or a map, could have a different effect in each case. This is where the power behind abstraction comes into play - we can write code in a general way, using abstract operations like conj with the confidence that it will work regardless of the concrete data type that we work with. While collections are the most general abstraction in ClojureScript, sequences are a narrower, more focused abstraction. Sequences allow us to think about data that can be considered linearly, which will be perfect for the products in this shopping cart example.

Sequences are a core abstraction in many of the domains that we as web developer work in. Whether it is a feed of blog posts, an email inbox, or a series of financial transactions, most applications have one or more sequences of data at their core. When we approach these types of programs from an object-oriented approach, we usually think first about the individual objects in the system and what behaviors they support. For instance, in the case of an email program, we might be inclined to start by creating a Message object with messages like markRead() or getLabels(). Once we have modeled these objects, we might build some sort of collection object to put them in, or we may just use an array and iterate over it. The ClojureScript way is a little different (and simpler). Instead of focusing on the individual behaviors of each granular object, we begin by thinking about the collective properties such as, “Which messages are read?", or “How many messages are in the inbox?”

Let’s take a step back and consider how we can think about the shopping cart problem in terms of sequences. First, we can model the cart as a vector of line items where each line item is a map with a :name and :price key.

cljs.user=> (def cart [{:name "Silicone Pancake Mold" :price 10.49}

{:name "Small Pour-Over Coffee Maker" :price 18.96}

{:name "Digital Kitchen Scale" :price 24.95}])

#'cljs.user/cart

Modeling a shopping cart

There are 2 properties that we need to know about this sequence. First, we need to know how to calculate sales tax for each item in the sequence, and second, we need to know how to sum all of the prices and all of the sales taxes. The general problems here are applying some operation to each element in a sequence and summarizing values from across a sequence into a single value. We can solve these problems with the functions map and reduce, respectively.

Transforming With Map

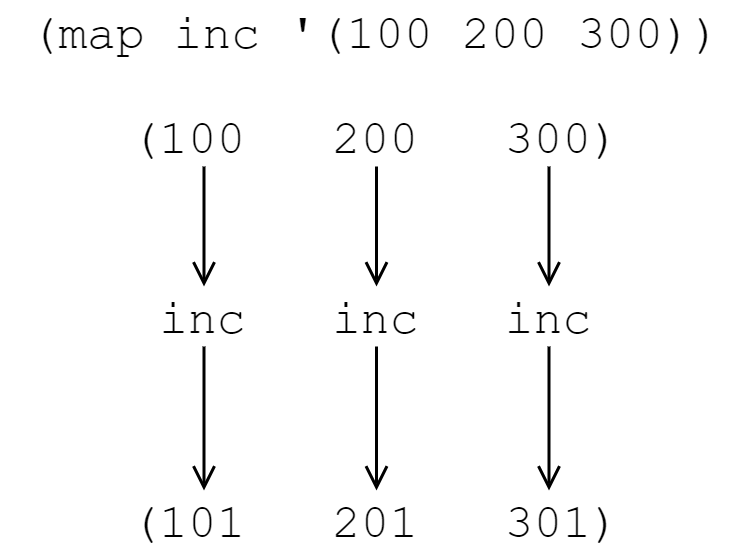

The map function takes a sequence and returns a new sequence in which every element corresponds to an element in the original sequence with some function applied to it. For instance, we can map the function inc - which gets the increment of an integer - over a list of numbers to get a new sequence in which each element is the increment of the corresponding number in the original sequence.

cljs.user=> (map inc '(100 200 300))

(101 201 301)

When we mapped the inc function over the list, (100 200 300), the result was a new list, (101, 201, 301). Each number in this new list is the increment of each element in the original list. You can imagine map as walking over a sequence, and as it comes to each element, it takes that element, passes it through a function, and puts the result into a new sequence. In this case, it applied inc to 100 and put the result, 101 into the new sequence. It did the same with the second and third elements, transforming 200 to 201 and 300 to 301. Finally, the call to map returned the list of all of the transformed numbers.

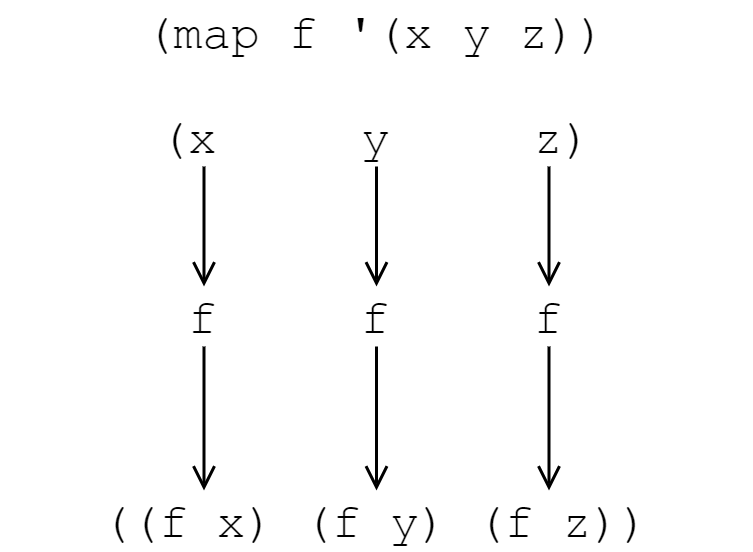

In general, map takes some function, f, and some sequence and returns a new sequence whose elements are the result of applying f to each element in the original sequence. Keep in mind that map returns a new sequence, so the original sequence is not touched. When the problem that we are working with involves any sort of a transformation of a sequence, map is usually the first tool that we should turn to. Many of the times that we would use a for loop in another language, we can use map in ClojureScript.

Quick Review

Take a look at the following code snippet:

(def samples [[8 12 4]

[9 3 3 6]

[11 4]])

(def result-1 (map first samples))

(def result-2 (map dec result-1))

- What is the value of

result-1? - What is the value of

result-2? - What is the value of

samples? - How would you get a collection with the length of each vector inside

samples?

Adding Sales Tax With Map

Coming back to our initial example of adding sales tax to a shopping cart, we will use map to create a new cart where each item is like an item in the original cart, but with the addition of a :sales-tax key. If we were using JavaScript, this would be an obvious case for a for loop, similar to the code below:

const taxRate = 0.079;

const cart = [ // <1>

{ name: "Silicone Pancake Mold", price: 10.49 },

{ name: "Small Pour-Over Coffee Maker", price: 18.96 },

{ name: "Digital Kitchen Scale", price: 24.95 },

];

for (let item of cart) { // <2>

item.salesTax = item.price * taxRate;

}

Adding Sales Tax Imperatively with JavaScript

- Define a cart as a list of products with a

nameandprice - Loop over every product in the cart, adding a new

salesTaxproperty

This code should feel very familiar for JavaScript programmers, as it just loops over an array and updates each element in-place. We updated the cart array in-place, which may have had an unintended consequence in some other part of the code that uses this array or any of the individual objects that it contains. What looked like a simple and innocuous piece of code could actually be the source of subtle bugs down the road.

We can use map to write a solution in ClojureScript (or JavaScript) that - in addition to being more concise - is simpler and less error-prone. Remember that map takes 2 arguments: a function to apply to each individual element, and a sequence. We already have a simple model of a shopping cart that we will use, so all that we need is a function to apply to each cart item that will produce a new item with sales tax added. Mapping this function over our shopping cart then becomes a one-liner.

cljs.user=> (def tax-rate 0.079)

#'cljs.user/tax-rate

cljs.user=> (defn add-sales-tax [cart-item] ;; <1>

(let [{:keys [price]} cart-item]

(assoc cart-item :sales-tax (* price tax-rate))))

#'cljs.user/add-sales-tax

cljs.user=> (add-sales-tax {:name "Medium T-Shirt" ;; <2>

:price 10.00})

{:name "Medium T-Shirt", :price 10, :sales-tax 0.79}

cljs.user=> (map add-sales-tax cart) ;; <3>

({:name "Silicone Pancake Mold", :price 10.49, :sales-tax 0.8287100000000001}

{:name "Small Pour-Over Coffee Maker", :price 8.96, :sales-tax 0.70784}

{:name "Digital Kitchen Scale", :price 24.95, :sales-tax 1.97105})

Adding Sales Tax With ClojureScript

- Define a function that transforms an item without sales tax into an item with sales tax

- Test this function on a single item

- Map this transformation over the entire cart to get a new cart with sales tax added

The meat of this code is in the add-sales-tax function, which takes a single cart item and returns an item with sales tax. One of the most important aspects of creating maintainable code is choosing good names, so we use a let expression to name the price of the item passed in simply price. On the next line, we use the assoc function to create a new map that is like cart-item but with the addition of one more entry whose key is :sales-tax and whose value is (* price tax-rate). assoc is an incredibly useful utility function that allows us to add or update a specific entry in an associative collection - that is, a collection that has the concept of keys that are associated with a value, most commonly maps. We pass assoc a collection (in this case, cart-item), the key that we wish to set, and the value to set it to, and the result is a new collection with the appropriate entry added or updated.

Next, we test this function on a single cart item to ensure that it works as expected. This test could be copied almost verbatim into a unit test suite to protect against regressions, but we will save that for another lesson. Finally, we get the result that we want with one simple expression: (map add-sales-tax cart). This expression reads almost like English, “Map the ‘sales-tax’ function over the ‘cart’ sequence.” There are no array indexes to maintain, no possibility of off-by-1 errors, overwriting variables, or unintended consequences of mutating cart. The solution, like all ClojureScript strives to be, is simple and concise.

You Try It

Now that we have seen how map works, let’s write some code to perform various transformations to the product list.

- Write a

mapexpression that returns a sequence of only the names of the products (hint: the:namekeyword acts as a function that looks up the:namekey in a map. - Write a

discountfunction that takes a list of products and a percent amount to deduct from the price of each product and returns a sequence of discounted products. You can fill in this template as a starting point:

(defn discount [products pct-discount]

(map (fn [product] ...) products))

Coercing Results With Into

There is one final “gotcha” that we need to be aware of with map and other sequence operations. As we can see in this example, cart is a vector, but the result of the call to map was something that looked like a list. That is no mistake - map, filter, and other sequence functions commonly accept any type of sequence as input but return a general data structure called a seq as a result. A seq is a general sequence type that behaves similarly to a list. When we build up a pipeline of functions to pass some sequence through, we generally don’t care about what data type is produced at each step, since we rely on the sequence abstraction to treat a vector in the same way as a list and a list in the same way as a seq, etc. A common ClojureScript idiom is to use the into function to convert a seq back into the type that we want afterwards:

cljs.user=> (def my-vec ["Lions" "Tigers" "Bears" "Lions"])

#'cljs.user/my-vec

cljs.user=> (defn loud [word]

(str word "!"))

#'cljs.user/loud

cljs.user=> (map loud my-vec) ;; <1>

("Lions!" "Tigers!" "Bears!" "Lions!")

cljs.user=> (into [] (map loud my-vec)) ;; <2>

["Lions!" "Tigers!" "Bears!" "Lions!"]

cljs.user=> (into '() (map loud my-vec)) ;; <3>

("Lions!" "Bears!" "Tigers!" "Lions!")

cljs.user=> (into #{} (map loud my-vec)) ;; <4>

#{"Lions!" "Tigers!" "Bears!"}

Coercing a Seq

- Mapping yields a seq

- The seq can be put into a new vector

- Putting the seq into a list reverses the elements

- Putting the seq into a set de-duplicates it

into takes a destination collection and a source collection and conjoins every element in the destination collection to the source collection. It walks over the source sequence one element at a time, using the same semantics as the conj function to add each element to the destination sequence. Since conj adds to the end of a vector but the beginning of a list, this explains why the elements in the resulting list is reversed. This pattern of coercing sequences with into is extremely common in ClojureScript, and we will use it extensively in later lessons.

Quick Review

As we have just learned, into repeatedly applies conj to add each element from some sequence into a collection. We need to be familiar with how conj works with different collections in order to understand the results of into.

- Re-write the following expression as a series of calls to

conj:(into [] '(:a :b :c)) - What is the result of

(conj (conj (conj '() 1) 2) 3) - What would change if we replaced the empty list,

'()in the previous exercise with an empty vector,[]?

Refining With Filter

We can now transform one sequence into another with map. There are many problems that we can solve with just this one tool, but consider the case where we don’t want to consider every element in a sequence - for instance, we are only interested in processing taxable items or users over the age of 21 or addresses in the state of Vermont. In these cases, map will not suffice, since map always produces a new sequence in which each element has a 1-to-1 correspondence to an element in the original sequence. This is where filter comes into play. Whereas we use map to transform a sequence in its entirety, we use filter to narrow down a sequence to only the elements that we are interested in.

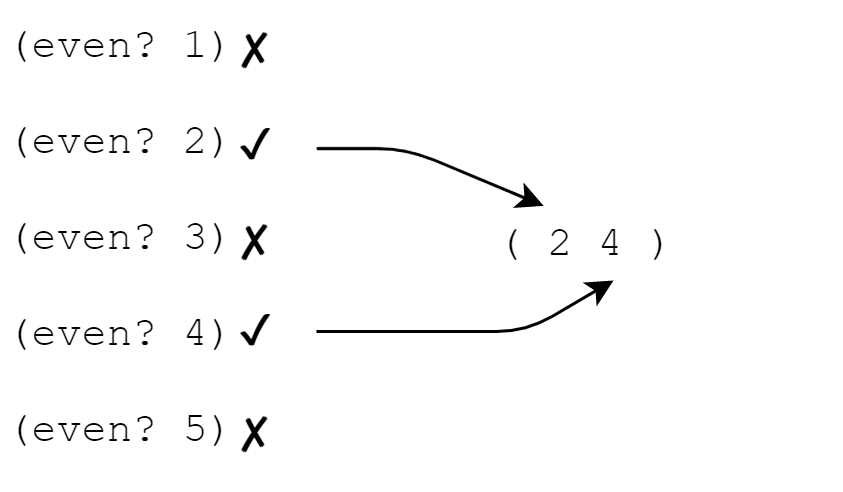

The filter function is fairly straightforward and similar to JavaScript’s Array.prototype.filter() function. It takes a function, f, and a sequence, xs and returns a new sequence of only the elements for which (f x) returns a truthy value. Again, this is one of those functions that is much easier to understand once we see it in action.

cljs.user=> (filter even? '(1 2 3 4 5)) ;; <1>

(2 4)

cljs.user=> (defn longer-than-4? [s] ;; <2>

(> (count s) 4))

#'cljs.user/longer-than-4?

cljs.user=> (filter longer-than-4? ;; <3>

["Life" "Liberty" "Pursuit" "of" "Happiness"])

("Liberty" "Pursuit" "Happiness")

Filtering a Sequence

- Filter a sequence with a standard library function

- Define a predicate (a function that returns a boolean) to use with filter

- Filter using the function we just defined

We can think of filter as inspecting the original sequence and only allowing certain elements through to the new sequence. It is kind of like a bouncer who enforces certain rules to determine who has access. If any element does not meet the criteria, they’re out! In the first example, we gave filter the criteria function (often called a predicate), even?, and a list of numbers. It checked each number in the list against the function even? and built up a new sequence from only the even numbers. This process is illustrated below:

Applying Filter to a Sequence

In the second example, we pass a function that we created to filter, but the process is exactly the same. The length of each string that we pass in is checked, and only words that exceed 4 characters are in the filtered sequence.

Finding Taxable Items With Filter

With this knowledge of how filter operates, it is simple to get only the taxable items from the shopping cart. First, we’ll update our cart model to include a :taxable? key on each item.

cljs.user=> (def cart [{:name "Silicone Pancake Mold" :price 10.49 :taxable? false}

{:name "Small Pour-Over Coffee Maker" :price 18.96 :taxable? true}

{:name "Digital Kitchen Scale" :price 24.95 :taxable? true}])

#'cljs.user/cart

Now let’s take a first pass at filtering the list to only the taxable items.

cljs.user=> (defn is-taxable? [item]

(get item :taxable?))

#'cljs.user/is-taxable?

cljs.user=> (filter is-taxable? cart)

({:name "Small Pour-Over Coffee Maker", :price 18.96, :taxable? true}

{:name "Digital Kitchen Scale", :price 24.95, :taxable? true})

Three lines of code (including the predicate function) to filter a sequence is not bad. Even better, there is no for loop in sight, which means that there is no room for off-by-one errors. This is pretty concise, but in ClojureScript, there is usually a way to make things more concise. Remember that keywords can be used as functions that look themselves up in a map. That means that if we call, (:taxable? {:name "Small Pour-Over Coffee Maker" :price 18.96 :taxable? true}), it will look up the :taxable? key in the map, {:name "Small Pour-Over Coffee Maker" :price 18.96 :taxable? true}, yielding true. This means that our is-taxable? function is redundant and can be replaced with just the keyword, :taxable?.

cljs.user=> (filter :taxable? cart)

({:name "Small Pour-Over Coffee Maker", :price 18.96, :taxable? true}

{:name "Digital Kitchen Scale", :price 24.95, :taxable? true})

We just accomplished filtering the list with a 1-liner that is every bit as clear as the previous version and is far simpler than the JavaScript alternative. Now we can really start to appreciate the simplicity that is so highly prized in the ClojureScript community.

Challenge

Data manipulation is one of ClojureScript’s strongest suits, but it does not serve much use until we somehow present it to the users of our system. Create a ClojureScript file that defines a shopping cart and renders a list of the name, price, and tax of every taxable product that it contains. One possible solution is below.

(ns shopping-cart.core

(:require [goog.dom :as gdom]))

(def tax-rate 0.079)

(def cart [{:name "Silicone Pancake Mold" :price 10.49 :taxable? false}

{:name "Small Pour-Over Coffee Maker" :price 18.96 :taxable? true}

{:name "Digital Kitchen Scale" :price 24.95 :taxable? true}])

(defn add-sales-tax [cart-item]

(assoc cart-item

:sales-tax (* (:price cart-item) tax-rate)))

(def taxable-cart

(map add-sales-tax

(filter :taxable? cart)))

(def item-list (gdom/createDom "ul" nil ""))

;; Helper function to generate the display text for a product

(defn display-item [item]

(str (:name item)

": "

(:price item)

" (tax: "

(.toFixed (:sales-tax item) 2)

")"))

;; Create the list of products

(doseq [item taxable-cart]

(gdom/appendChild

item-list

(gdom/createDom "li" #js {} (display-item item))))

;; Clear the entire document and append the list

(gdom/removeChildren (.-body js/document))

(gdom/appendChild (.-body js/document) item-list)

Rendering a Shopping Cart

Summary

In this lesson, we started to feel the power of programming using the high-level sequence abstraction. We learned that most of the places where we would use a for loop in JavaScript can be expressed more clearly and concisely with a sequence operation. Finally we put this knowledge to use in creating a shopping cart component that renders items in a cart with sales tax. The operations that we looked at in this lesson all took a sequence in and evaluated to a new sequence. In the next lesson, we will look at another useful class of problems that take a sequence in and evaluate to a scalar value.