Lesson 20: Capstone 3 - Contact Book

Over the past few lessons, we have learned the core tools for working with data in ClojureScript. First, we learned about the basic collection types - lists, vectors, maps, and sets - as well as the most common functions for working with these collections. Then we took a closer look at the important sequence abstraction that allows us to operate on all sorts of sequential data using a uniform interface. Next, we discovered the reduce function and the many cases in which it can be used to summarize a sequence of data. Last, we walked through the process of modeling a real- world analytics domain. With this knowledge in our possession, we are ready to build another capstone project. This time, we will take the example of a contact book that we mentioned back in Lesson 16, and we will build a complete implementation, ClojureScript Contacts.

In this lesson:

- Create a complete ClojureScript application without any frameworks

- Build HTML out of plain ClojureScript data structures

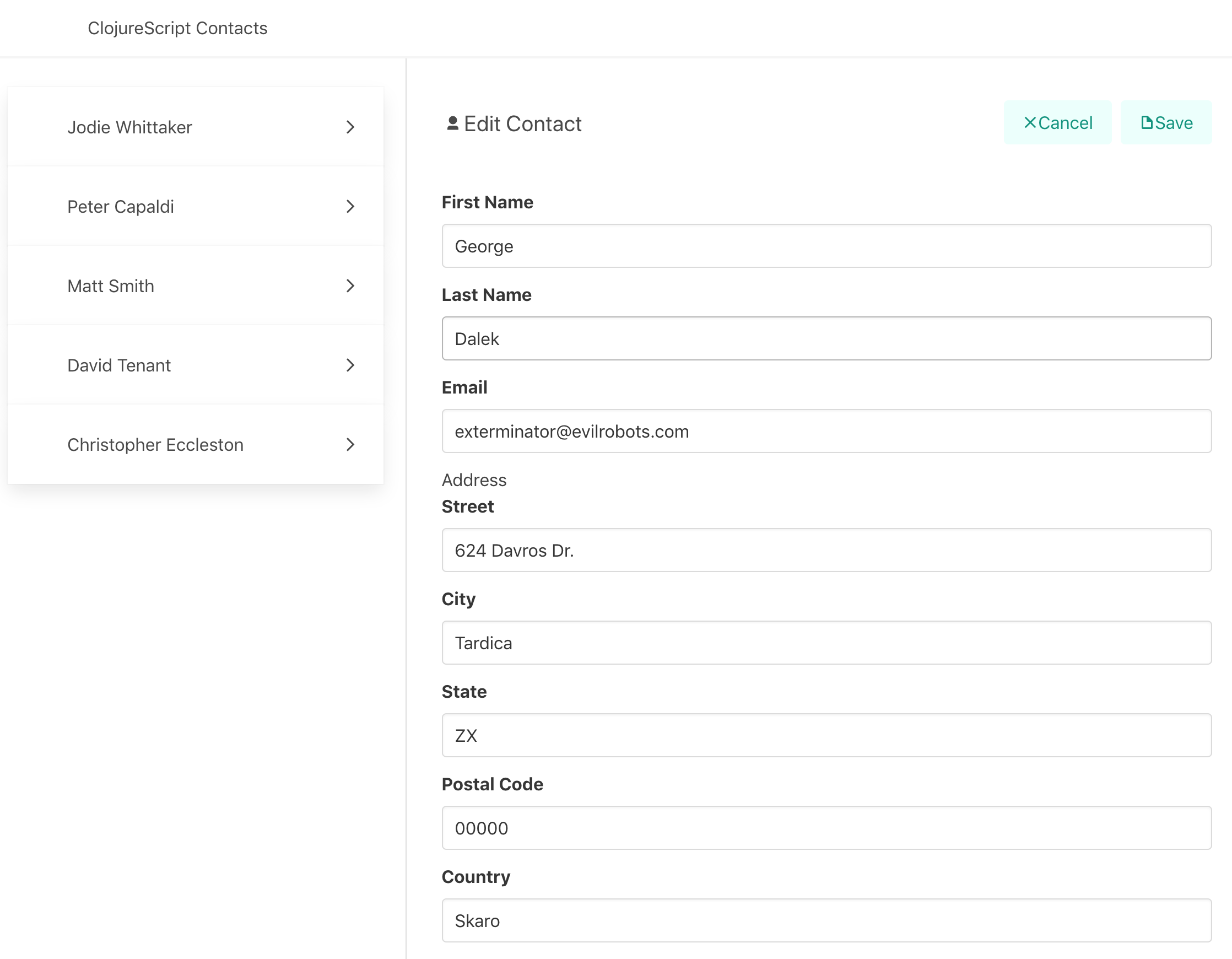

Screenshot of ClojureScript Contacts

While we will not be printing the code for this capstone in its entirety, the completed project code may be found at the book’s GitHub repository. As we have done previously, we will create a new Figwheel project:

$ clj -X:new :template figwheel-main :name learn-cljs/contacts :args '["+deps"]'

$ cd contacts

$ clj -A:fig:build

Data Modeling

In this lesson, we will use the techniques and patterns from the previous chapter to model the data for our contact book. The goal will be to practice what we have learned rather than to introduce much new material. We will primarily model our data using maps and vectors, and we will implement the constructor function pattern for creating new contacts. We will also implement the operations that the UI will need to update the contact list using simple functions to transform our data. With that, let’s dig in to the data model!

Constructing Entities

Since a contact book represents an ordered list of contacts, we will need a data structure to represent that ordered list, and as we have already seen, a vector fits the bill nicely. We can define an empty contact list as an empty vector - no constructor function necessary:

(def contact-list [])

Since an empty vector is not terribly interesting, let’s turn our attention to the contacts that it will hold. Each contact will need a first name, last name, email address, and a physical address, including city, state, and country. This can easily be accommodated with a nested map, such as the following:

{:first-name "Phillip"

:last-name "Jordan"

:email "phil.j@hotmail.com"

:address {:street "523 Sunny Hills Cir."

:city "Springfield"

:state "MI"

:postal "11111"

:country "USA"}}

In order to construct a new contact, we will use a variation on the constructor pattern introduced in the last lesson. Instead of passing in each field individually, we will pass in a map that we expect to contain zero or more of the fields that make up a contact. You will recall from the last lesson that the select-keys function takes a map and a collection of keys that should be selected, and it returns a new map with only the selected keys copied. We can use this function to sanitize the input, ensuring that our contact contains only valid keys.

(defn make-contact [contact]

(select-keys contact [:first-name :last-name :email :postal :address]))

Since the address itself is a map, let’s factor out creation of an address to another function. We can then update the make-contact function to use this address constructor:

(defn make-address [address]

(select-keys address [:street :city :state :country]))

(defn make-contact [contact]

(let [clean-contact (select-keys contact [:first-name :last-name :email])]

(if-let [address (:address contact)]

(assoc clean-contact :address (make-address address))

clean-contact)))

This new version of make-contact introduces one expression that we have not seen before: if-let. This macro works just like if except that it binds a name to the value being tested (just like let does). Unlike let, only a single binding may be provides. At compile time, this code will expand to something like the following1:

(if (:address contact)

(let [address (:address contact)]

(assoc clean-contact :address (make-address address)))

clean-contact)

if-let Transformation

We will soon make use of a similar macro, when-let. Like if-let, it allows a binding to be provided, and like when, it only handles the case when the bound value is non-nil.

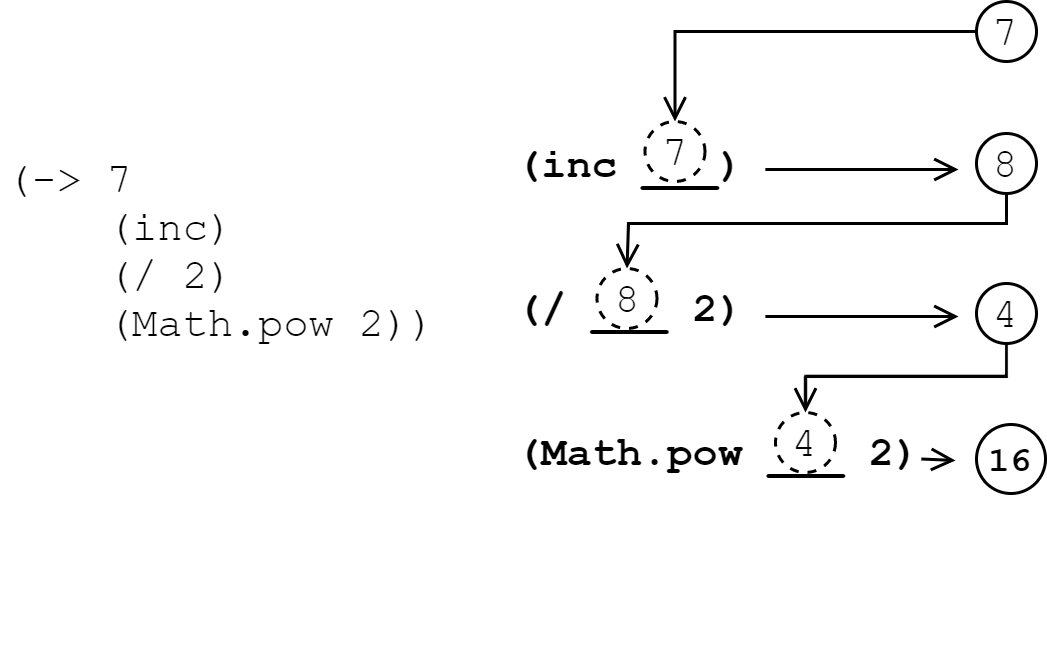

However, we can make the make-contact function a bit more concise and easier to read using one of ClojureScript’s threading macros, -> (pronounced “thread first”). This macro allows us to take what would otherwise be a deeply nested expression and write it more sequentially. It takes a value and any number of function calls and injects the value as the first argument to each of these function calls. Seeing this transformation in action should make its functionality more intuitive:

(-> val ;; <1>

(fn-1 :foo) ;; <2>

(fn-2 :bar :baz) ;; <3>

(fn-3))

(fn-3 ;; <4>

(fn-2

(fn-1 val :foo)

:bar :baz))

Thread-First Transformation

- Start with

valas the value to thread through the following expressions fn-1will be evaluated with the arguments,valand:foo- The result of the evaluation of

fn-1will be threaded as the first argument tofn-2 - The macro will rewrite into a nested expression that evaluates

fn-1thenfn-2, thenfn-3

This macro is extremely common in ClojureScript code because of how it enhances the readability of our code. We can write code that looks sequential but is evaluated “inside-out”. There are several additional threading macros in ClojureScript that we will not go into now, but we will explain their usage as we run into them.

Thread First Macro

With this macro, we can make our make-contact function even clearer:

(defn maybe-set-address [contact] ;; <1>

(if (:address contact)

(update contact :address make-address)

contact))

(defn make-contact [contact]

(-> contact ;; <2>

(select-keys [:first-name :last-name :email])

(maybe-set-address)))

- Refactor the code that conditionally constructs an address

- Rewrite

make-contactusing the->macro

Quick Review

- Does

if-letallow multiple bindings? For example, what would this code do?

(if-let [contact (find-by-id 123)

address (:address contact)]

(println "Address:" (format-address address)))

- How would the

->macro rewrite the following expression?

(let [input {:password "s3cr3t"}]

(-> input

(assoc :password-digest (-> input :password digest))

(dissoc :password)))

Defining State Transitions

In order for our UI to do anything other than display a static list of contacts that we define in code, we need to enable some interactions in the UI. Again, we are building our low-level domain logic before any UI code so that we can take advantage of the bottom-up programming style that ClojureScript encourages - composing small, granular functions into larger and more useful structures.

First, we want the user to be able to add a new contact to the contact list. We can assume that we will receive some sort of form data as input, which we can pass to our make-contact constructor, adding the resulting contact to our list. We will need to pass in the contact list and input data as arguments and produce a new contact list.

(defn add-contact [contact-list input]

(conj contact-list

(make-contact input)))

We can paste these function definitions into the REPL and then test them to make sure that they function as expected:

cljs.user=> (-> contact-list ;; <1>

(add-contact {:email "me@example.com"

:first-name "Me"

:address {:state "RI"}})

(add-contact {:email "you@example.com"

:first-name "You"}))

[{:first-name "Me", :email "me@example.com"}

{:first-name "You", :email "you@example.com"}]

Testing with the REPL

- Once again, the

->macro makes our code easier to read and write

Next, we will need a way to remove a contact from the list. Since we are using a vector to hold our contacts, we can simply remove an element at a specific index:

(defn remove-contact [contact-list idx]

(vec ;; <1>

(concat ;; <2>

(subvec contact-list 0 idx) ;; <3>

(subvec contact-list (inc idx)))))

Removing a Contact

vecconverts a sequence into a vectorconcatreturns aseqthat contains all elements in the sequences passed to it in ordersubvecreturns a portion of the vector that it is given

Since there are a couple of new functions here that we have not seen yet, let’s quickly look at what they do. Starting from the “inside” of this function, we have subvec. This function provides an efficient way to obtain a slice of some vector. It comes in a 2-arity and a 3-arity form: (subvec v start) and (subvec v start end). This function work similarly to JavaScript’s Array.prototype.slice() function. It returns a new vector that starts at the start index of the original vector and contains all elements up to but not including the end index. If no end is provided, it will contain everything from start to the end of the original vector.

Next, we have concat. This function takes a number of sequences and creates a new lazy2 seq that is the concatenation of all of the elements of its arguments. Because the result is a seq, we use the vec function to coerce the result back into a vector. Since much of ClojureScript’s standard library operates on the sequence abstraction, we will find that we often need to convert the result back into a more specific type of collection.

Finally, when we update a contact, we want to replace the previous version. This can be done by using assoc to put the updated contact in the same index of contact-list that was occupied by the old version:

(defn replace-contact [contact-list idx input]

(assoc contact-list idx (make-contact input)))

Quick Review

- We mentioned that

vecconverts a sequence into a vector. Given what we learned about the sequence abstraction, what will happen if you passveca map? What about a set?

Creating the UI

Now that we have defined all of the functions that we need to work with our data model, let’s turn our attention to creating the application UI. In Section 5, we will learn how to create high-performance UIs using the Reagent framework, but for now, we will take naive approach of re-rendering the entire application whenever anything changes. Our application will have two main sections - a list of contacts that displays summary details about each contact and a larger pane for viewing/editing contact details.

We will use the hiccups library to transform plain ClojureScript data structures into an HTML string. This allows us to represent the interface of our application as a ClojureScript data structure and have a very simple interface to the actual DOM of the page. In order to use this library, we need to add it to our dependencies in deps.edn:

:deps {;; ...Other dependencies

hiccups/hiccups {:mvn/version "0.3.0"}}

deps.edn

Then, we need to import this library into our core namespace. Note that since we are using a macro from this library, the syntax is a little different:

(ns learn-cljs.contacts

(:require-macros [hiccups.core :as hiccups])

(:require [hiccups.runtime]))

learn_cljs/contacts.cljs

The translation between ClojureScript data structures and HTML is very simple:

- HTML tags are represented by vectors whose first element is the tag name as a keyword

- Attributes are represented by maps and should come immediately after the tag name. Omitting attributes is fine.

- Any remaining elements in the vector are children of the outer element

For example, the following code renders a div containing a single anchor tag:

(hiccups/html ;; <1>

[:div ;; <2>

[:a {:href "https://www.google.com" ;; <3>

:class "external-link"}

"Google"]]) ;; <4>

;; <div><a class="external-link" href="https://www.google.com">Google</a></div>

Rendering With Hiccups

- The

htmlmacro renders hiccups data to an HTML string - Create a

div. We do not need to specify any attributes - Create an

aelement with an attributes map as a child of the outerdiv - The

aonly contains text

With this knowledge, we can start defining components for our various UI elements that produce a hiccups-compatible data structure. We can compose these functions together to create a data structure that represents the entire UI, and we’ll pass this to another function that renders the whole structure to the page.

UI State

Let’s take a quick step back and think about the additional state that we need for the UI. First, we need to have a flag indicating whether we are in editing mode. In editing mode, a form with contact details will be displayed in the right-hand pane. Also, we need to keep track of which contact has been selected for editing - in the case of a new contact that has not been saved yet, this property will be nil or omitted. Naturally, we also need the contacts on the application state. This leaves us with a pretty simple state model to support everything that we want in our UI:

(def initial-state

{:contacts contact-list

:selected nil

:editing? false})

We will also define a refresh! function that is responsible for rendering the entire application and attaching event handlers every time our state changes. We must re-attach event handlers because we are replacing the DOM tree that contains our app, and our handlers remain attached to the DOM nodes that are discarded.

(defn attach-event-handlers! [state]) ;; <1>

(defn set-app-html! [html-str]

(set! (.-innerHTML app-container) html-str))

(defn render-app! [state]

(set-app-html!

(hiccups/html

[:div]))) ;; <2>

(defn refresh! [state] ;; <3>

(render-app! state)

(attach-event-handlers! state))

(refresh! initial-state) ;; <4>

- All event handlers that we need to attach will be attached in this function

- We will replace the empty div with our actual application HTML

refresh!will be called every time that we update the application state- We kick off the application with an initial

refresh!to render the page frominitial-state

Rendering Contacts

Let’s start with the component that displays the contact summary in the list. We will be using the Bulma CSS framework to help with styling3, so most of the markup that we are generating is for the purpose of styling the page. Additionally, we will be using the Microns icon font, which uses mu-ICON class names.

(defn format-name [contact] ;; <1>

(->> contact ;; <2>

((juxt :first-name :last-name)) ;; <3>

(str/join " ")))

(defn delete-icon [idx]

[:span {:class "delete-icon"

:data-idx idx}

[:span {:class "mu mu-delete"}]])

(defn render-contact-list-item [idx contact selected?]

[:div {:class (str "card contact-summary" (when selected? " selected"))

:data-idx idx} ;; <4>

[:div {:class "card-content"}

[:div {:class "level"}

[:div {:class "level-left"}

[:div {:class "level-item"}

(delete-icon idx)

(format-name contact)]]

[:div {:class "level-right"}

[:span {:class "mu mu-right"}]]]]])

Rendering a Contact Summary

- Extract the logic for a contact’s display name into another function

- Use the

->>(thread last) macro to pass a value through as the last argument to each subsequent function - The

juxtfunction extracts the first and last name from the contact. It is described below idxis needed so that we will be able to get the correct contact in our event handlers

Both of the things that we should note about this code occur in the format-name function. First, we use the ->> macro to thread a value through several function calls. This works almost exactly like the -> macro that we used earlier in this lesson with the exception that it feeds threads the value as the last argument to each subsequent function.

Second, the juxt function is a very interesting function that deserves a bit of an explanation. juxt takes a variable number of functions and returns a new function. This resulting function will call each of the original functions passed to juxt in turn using the arguments provided to it. The results are finally placed into a vector in the same order as the functions that were passed to juxt. For example, this code snippet will create a function that will get 2-element vector containing the minimum and maximum values from a collection:

(def minmax

(juxt #(reduce Math/min %)

#(reduce Math/max %)))

(minmax [48 393 12 14 -2 207])

;; [-2 393]

The reason for the extra set of parentheses in the call to juxt - ((juxt :first-name :last-name)) - is that we need to call the function returned by juxt rather than threading the contact into the call to juxt itself. Since keywords are functions that can look themselves up in maps, this expression will effectively create a vector with the first name and last name of the contact respectively.

((juxt :first-name :last-name) {:first-name "Bob" :last-name "Jones"})

;; ["Bob" "Jones"]

Adding Interactions

Let’s now think about the interactions that we want to enable on the contact summary. When the row is clicked, we want to open up this contact’s details for view/editing. We will attach an event handler to each list item that will set an :editing? flag on the app state and will set :selected to the index of the contact that was clicked (this is why we needed to pass idx into the rendering function and set the data-idx attribute on the row).

(defn on-open-contact [e state]

(refresh!

(let [idx (int (.. e -currentTarget -dataset -idx))]

(assoc state :selected idx

:editing? true))))

(defn attach-event-handlers! [state]

;; ...

(doseq [elem (array-seq (gdom/getElementsByClass "contact-summary"))]

(gevents/listen elem "click"

(fn [e] (on-open-contact e state)))))

We should be familiar with the use of doseq to eagerly iterate over a sequence, but this is the first time we have seen array-seq. This function takes a JavaScript array and transforms it into a ClojureScript seq that can be used with any sequence operation - in this case, doseq.

Now that we can render a single contact list item, let’s create the list that will display each list item:

(defn render-contact-list [state]

(let [{:keys [:contacts :selected]} state]

[:div {:class "contact-list column is-4 hero is-fullheight"}

(map-indexed (fn [idx contact]

(render-contact-list-item idx contact (= idx selected)))

contacts)]))

This function is pretty straightforward: it renders a wrapper div with each contact list item, then it delegates to the render-contact-list-item function to render the summary for each contact in turn. There is a new function that we have not yet met, however: map-indexed. This function works just like map except that it calls the mapping function with the index of the element in the sequence as well as the element itself.

This pattern of building a UI by composing components is common in the JavaScript world as well, but in most ClojureScript applications, the method of composing UIs is function composition with pure functions that produce plain data structures.

Finally, we will briefly cover rendering the contact details form and adding/updating contacts without too much additional explanation. First, let’s look at the function that renders the entire app HTML:

(defn render-app! [state]

(set-app-html!

(hiccups/html

[:div {:class "app-main"}

[:div {:class "navbar has-shadow"}

[:div {:class "container"}

[:div {:class "navbar-brand"}

[:span {:class "navbar-item"}

"ClojureScript Contacts"]]]]

[:div {:class "columns"}

(render-contact-list state)

[:div {:class "contact-details column is-8"}

(section-header (:editing? state))

[:div {:class "hero is-fullheight"}

(if (:editing? state)

(render-contact-details (get-in state [:contacts (:selected state)] {}))

[:p {:class "notice"} "No contact selected"])]]]])))

We have already seen the render-contact-list function, but we still need to define section-header, which will display the buttons for adding or saving a contact, and render-contact-details, which will render the edit form. Let’s start with render-contact-details:

(defn form-field ;; <1>

([id value label] (form-field id value label "text"))

([id value label type]

[:div {:class "field"}

[:label {:class "label"} label]

[:div {:class "control"}

[:input {:id id

:value value

:type type

:class "input"}]]]))

(defn render-contact-details [contact]

(let [address (get contact :address {})] ;; <2>

[:div {:id "contact-form" :class "contact-form"}

(form-field "input-first-name" (:first-name contact) "First Name")

(form-field "input-last-name" (:last-name contact) "Last Name")

(form-field "input-email" (:email contact) "Email" "email")

[:fieldset

[:legend "Address"]

(form-field "input-street" (:street address) "Street")

(form-field "input-city" (:city address) "City")

(form-field "input-state" (:state address) "State")

(form-field "input-postal" (:postal address) "Postal Code")

(form-field "input-country" (:country address) "Country")]]))

Rendering Contact Details

- Since we will be rendering multiple form fields, we will extract the code for a field into its own function

- The address may or may not be present, so we provide an empty map as a default

Now let’s look at the code for processing the form and either adding or updating a contact:

(defn get-field-value [id]

(let [value (.-value (gdom/getElement id))]

(when (not (empty? value)) value)))

(defn get-contact-form-data []

{:first-name (get-field-value "input-first-name")

:last-name (get-field-value "input-last-name")

:email (get-field-value "input-email")

:address {:street (get-field-value "input-street")

:city (get-field-value "input-city")

:state (get-field-value "input-state")

:postal (get-field-value "input-postal")

:country (get-field-value "input-country")}})

(defn on-save-contact [state]

(refresh!

(let [contact (get-contact-form-data)

idx (:selected state)

state (dissoc state :selected :editing?)] ;; <1>

(if idx

(update state :contacts ;; <2>

replace-contact idx contact)

(update state :contacts

add-contact contact)))))

statewithin theletwill refer to this updated state- Use our domain functions to update the contact list within our app state

Before moving on, let’s take a look at the use of update to transform our application state. update takes an indexed collection (a map or vector), a key to update, and a transformation function. This function is variadic, and any additional arguments after the transformation function that will be passed to the transformation function following the value to transform. For instance, the call, (update state :contacts replace-contact idx contact), will call replace-contact with the contacts list followed by idx and contact.

Now, we will finally implement the page header with its actions to create and save contacts:

(defn action-button [id text icon-class]

[:button {:id id

:class "button is-primary is-light"}

[:span {:class (str "mu " icon-class)}]

(str " " text)])

(def save-button (action-button "save-contact" "Save" "mu-file"))

(def cancel-button (action-button "cancel-edit" "Cancel" "mu-cancel"))

(def add-button (action-button "add-contact" "Add" "mu-plus"))

(defn section-header [editing?]

[:div {:class "section-header"}

[:div {:class "level"}

[:div {:class "level-left"}

[:div {:class "level-item"}

[:h1 {:class "subtitle"}

[:span {:class "mu mu-user"}]

"Edit Contact"]]]

[:div {:class "level-right"}

(if editing?

[:div {:class "buttons"} cancel-button save-button]

add-button)]]])

(defn on-add-contact [state]

(refresh! (-> state

(assoc :editing? true)

(dissoc :selected))))

(defn replace-contact [contact-list idx input]

(assoc contact-list idx (make-contact input)))

(defn on-save-contact [state]

(refresh!

(let [contact (get-contact-form-data)

idx (:selected state)

state (dissoc state :selected :editing?)]

(if idx

(update state :contacts replace-contact idx contact)

(update state :contacts add-contact contact)))))

(defn on-cancel-edit [state]

(refresh! (dissoc state :selected :editing?)))

(defn attach-event-handlers! [state]

;; ...

(when-let [add-button (gdom/getElement "add-contact")]

(gevents/listen add-button "click"

(fn [_] (on-add-contact state))))

(when-let [save-button (gdom/getElement "save-contact")]

(gevents/listen save-button "click"

(fn [_] (on-save-contact state))))

(when-let [cancel-button (gdom/getElement "cancel-edit")]

(gevents/listen cancel-button "click"

(fn [_] (on-cancel-edit state))))))

By now, this sort of code should be no problem to read and understand. In the interest of space, we will not reprint the entire application code, but it can be found at the book’s GitHub project.

You Try It

- Allow contacts to have phone numbers. Each phone number will need a

:typeand:number. This will require updates to the models, components, and event handlers.

Summary

While this application is not a shining example of modern web development (don’t worry - we will get to that in Section 5), it showed us how to build a data-driven application using the techniques that we have been learning in this section. While this is not a large application, it is a non-trivial project that should have helped us get more familiar with transforming data using ClojureScript. Still, much of our ClojureScript code still looks a lot like vanilla JavaScript with a funky syntax. In the next section, we will start to dig in to writing more natural, idiomatic ClojureScript.