Lesson 21: Functional Programming Concepts

ClojureScript sits at the intersection of functional programming and pragmatism. In this lesson, we will take a deeper look at what it means to be a functional language. As we shall see, functional programming is about much more than simply being able to use functions as values. At its core, the more important concepts are composability, functional purity, and immutability. Composability means that we build larger modules and systems out of small, reusable pieces. The concept of functional purity means that our functions do not have side effects like mutating global state, modifying the web page, etc. Immutability means that instead of modifying variables in-place, we produce new, transformed values. These three concepts together make for effective functional programming, and by the end of this lesson, we will have a better understanding of what it means to write functional code in ClojureScript.

In this lesson:

- Apply bottom-up design by composing small functions into larger ones

- Make programs easier to reason about with functional purity

- Learn the key role that immutability plays in functional programming

Composing Behavior from Small Pieces

In imperative programming, we often keep some sort of mutable state and write functions that operate on this state. The key insights introduced by object-oriented programing is that programs are easier to reason about when we encapsulate our mutable state with the methods that are allowed to operate on that state into an object. Clean object-oriented code is factored into methods that have only a single responsibility. While this may sound good on the surface, it often ends up being both more and less restrictive than we desire. It is more restrictive than we would like because it is difficult to share similar logic between multiple objects without introducing significant complexity. It is less restrictive than we would like because any of these methods may change the state of the object to which they belong such that the future behavior of any method on the object may be altered in a way that the caller does not anticipate.

Like object-oriented programming, functional programming encourages writing functions that do one thing, but it does not suffer from the two deficiencies stated above. Instead, functions may operate on any data without having to be encapsulated into an object, which leads to simpler code with less duplication. Additionally, pure functions by definition do not modify any state, and their behavior cannot be affected by any mutable state, so their behavior is well-defined in all cases.

When our data is modeled using common data structures (primarily maps and lists), and we do not rely on shared mutable state, something very interesting occurs: we can compose a handful of functions in many, many ways. In fact, we can often create our programs without doing much outside of composing functions from the standard library. At this point, we must include the quote that must make an appearance in every good text on functional programming to further this point:

It is better to have 100 functions operate on one data structure than to have 10 functions operate on 10 data structures.- Alan Perlis

What Perlis means is that when we have 100 functions that operate on the same common data type or abstraction, we can compose them to do many more than 100 things. However, if we go the object-oriented route and tie methods to specific classes of objects, then the ways in which we compose behavior is much more limited.

As we will be building a group chat application at the end of this section, let’s consider a component that displays a user’s “badge”, which is essentially their nickname and their current online status.

User Status Badge

We can break this component down into a couple of small composable pieces. First, let’s write functions that will get a user’s nickname as well as a function that wraps any hiccup-like structure that we give it in a strong tag to make it bold.

(def alan-p {:first-name "Alan" ;; <1>

:last-name "Perlis"

:online? false})

(defn nickname [entity] ;; <2>

(or (:nickname entity)

(->> entity

((juxt :first-name :last-name))

(s/join " "))))

(defn bold [child] ;; <3>

[:strong child])

(bold (nickname alan-p))

;; => [:strong "Alan Perlis"]

- Define sample data

- Extract a user’s nickname

- Make some DOM bold

Next, since we know that we will want to add classes to certain elements for styling purposes, we can create a function to add a class to any hiccup-like tag.

(defn concat-strings [s1 s2]

(s/trim (str s1 " " s2)))

(defn with-class [dom class-name]

(if (map? (second dom))

(update-in dom [1 :class] concat-strings class-name)

(let [[tag & children] dom]

(vec (concat [tag {:class class-name}]

children)))))

Since we are using plain data structures to represent the DOM, this function can be written in terms of data manipulation functions from the standard library. In fact, it does not refer to anything specific to hiccup at all! Now we can write a function that adds an “online” or “offline” class to the user badge based on the value of the user’s online? flag:

(defn with-status [dom entity]

(with-class dom

(if (:online? entity) "online" "offline")))

Note that even though we are inspecting the online? property of a user, there is nothing preventing us from using this function on entities that we want to add in the future, such as chatbots. Finally, we can define a user-status component almost purely in terms of these small building blocks that we just created:

(defn user-status [user]

[:div {:class "user-status"}

((juxt

(comp bold nickname) ;; <1>

(partial with-status ;; <2>

[:span {:class "status-indicator"}]))

user)])

compcreates a new function that composes others togetherpartialcreates a function that already has some arguments supplied

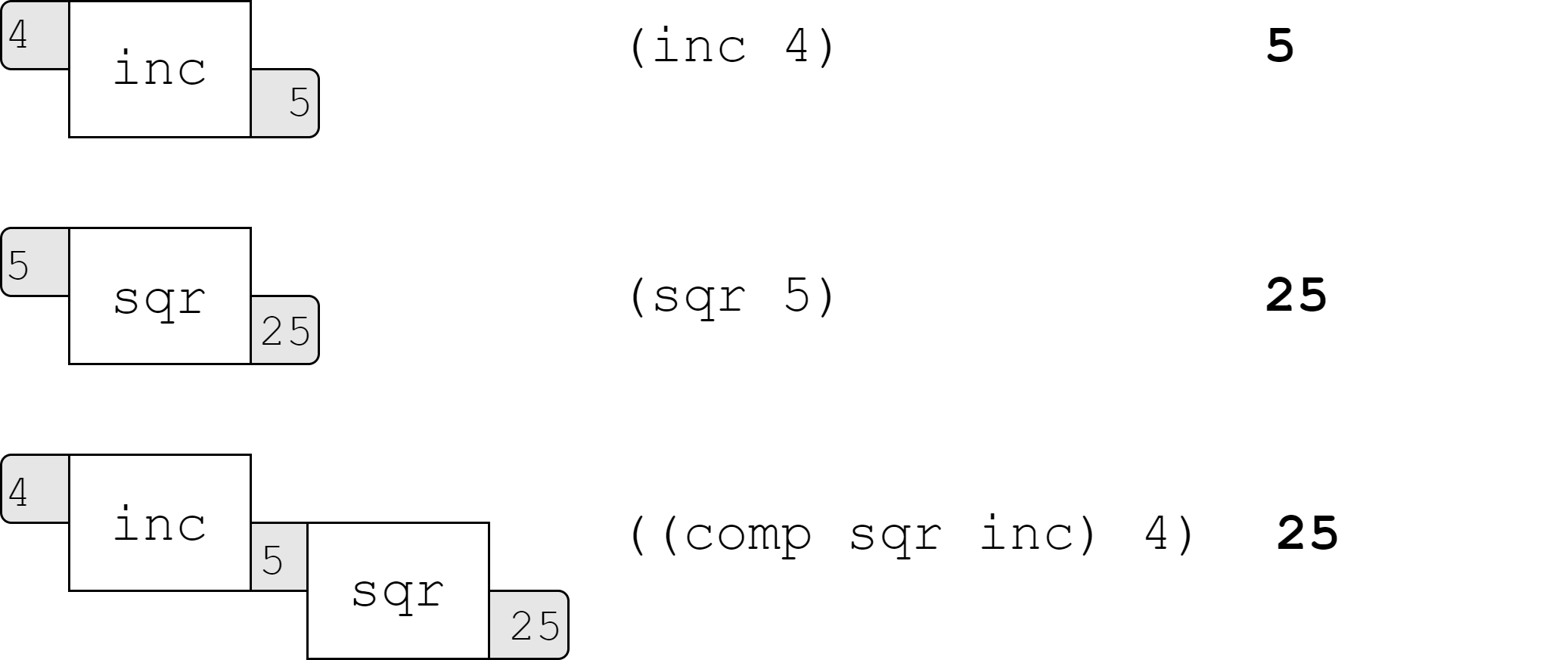

We first saw juxt in the last lesson, but there are two more functions in this example that are used very commonly in ClojureScript and are incredibly useful in combining smaller functions into larger applications: comp and partial. comp performs function composition, similar to mathematical function composition:

Mathematical Function Composition

As in mathematics, composing functions f and g creates a function that when applied to some argument, x, evaluates (g x) and then passes that result as the argument to f, as in the following example.

(= ((comp f g) x)

(f (g x)))

Function Composition in ClojureScript

We can think of comp as similar to the -> macro applied in reverse, except that rather than evaluating the entire pipeline of functions, it produces a new function that will evaluate the pipeline with any input that we give it. In the case of our user status component, we use (comp bold nickname) to create a function that will take a user and return a bolded version of that user’s nickname. We can think of the new function as a pipeline that connects each function from right to left.

comp Function Pipeline

The other new function that we used is partial. While partial is not directly related to function composition, it does give us the ability to take a general function and create a more specified version of it by supplying one or more of its parameters. The canonical example of partial application is the addition function: (add x y). We can use partial to supply the x argument, creating a new function that only takes y and adds the x that we already supplied:

(defn add [x y] ;; <1>

(+ x y))

(def add-5 (partial add 5)) ;; <2>

(add-5 10)

;; 15

- Define our own add function that only has 2 parameters

- Create a partially applied version

In this example, partial generates a new function that will call add with 5 plus any other argument that we give it. The call to partial is functionally equivalent to the following definition:

(def add-5

(fn [y]

(add 5 y)))

This trivial example of building a user status component out of small, composable functions that operate on simple data should illustrate the power of function composition to create an extensible, reusable codebase.

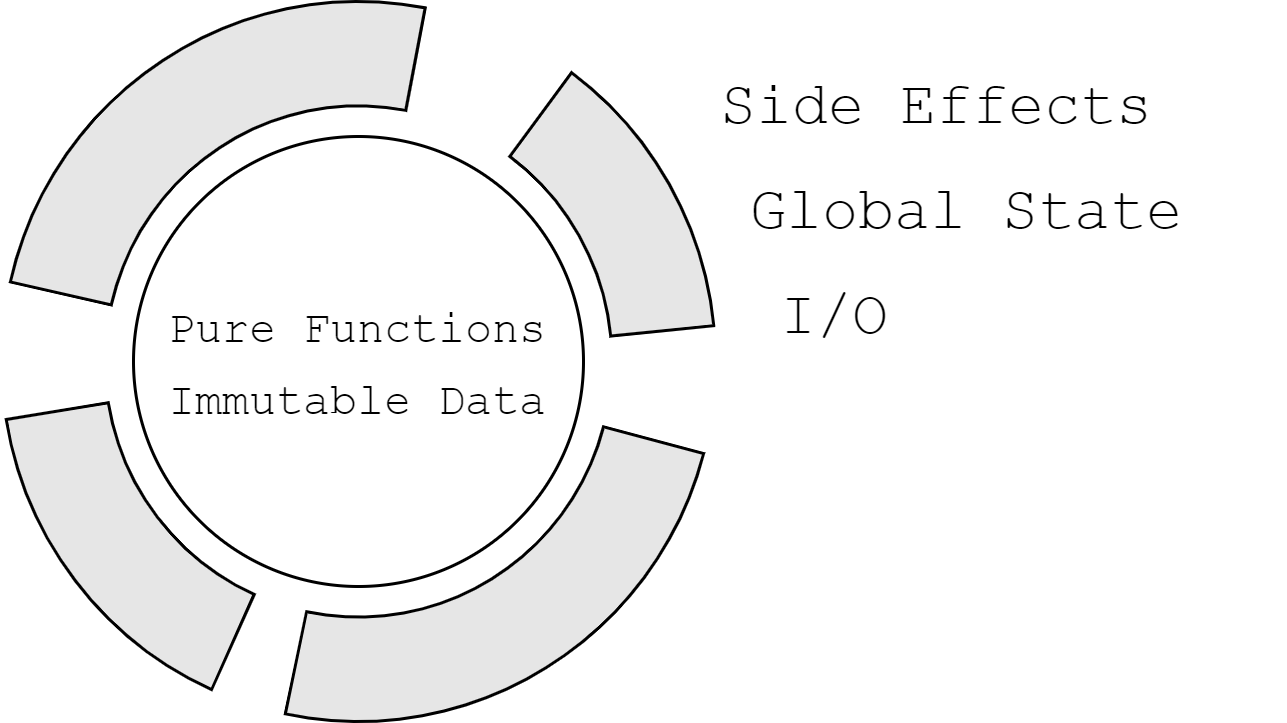

Writing Pure Functions

Side effects are essential in every useful program. A program with no side effects could not modify the DOM, make API requests, save data to localStorage, or any of the other things that we typically want to do in a web application. Why, then, do we talk about writing code without side effects as a good thing? The purely functional programming model does not allow side effects, but all functional programming languages provide at least some facility for side effects. For instance, Haskell provides the IO monad for performing impure IO operations behind an otherwise pure functional API. ClojureScript is even more practical though, allowing us to write side-effecting code as needed. If we were not careful, we could end up writing code that has all of the same pitfalls as most JavaScript code in the wild. Since the language itself is not going to prevent us from writing code riddled with side effects, we need to intentionally constrain ourselves to write mostly pure applications. Thankfully, ClojureScript makes that sort of constraint easy.

Keeping a Purely Functional Core

While we need side effects, we should strive to segregate functions that perform side effects from those that can be pure. The pure functions can then be easily tested and reasoned about. For instance, let’s take a look at the code that we wrote for the temperature converter app in Lesson 15:

(defn update-output [_]

(if (= :celsius (get-input-uom))

(do (set-output-temp (c->f (get-input-temp)))

(gdom/setTextContent output-unit-target "F"))

(do (set-output-temp (f->c (get-input-temp)))

(gdom/setTextContent output-unit-target "C"))))

While this code gets the job done, it is not especially clean or elegant because it both performs a conversion and does I/O. In order to test this code, we need to run it on a page where all of the elements exist, and in order to test it, we would have to manually set the input fields, call the function, then assert on the content of the output element. Instead, we could refactor this into several pure functions: a pure function to get the label, a pure function to perform the conversion, and an impure function that reads from and mutates the DOM.

(defn target-label-for-input-unit [unit] ;; <1>

(case unit

:fahrenheit "F"

:celsius "C"))

(defn convert [unit temp] ;; <2>

(if (= :celsius unit)

(c->f temp)

(f->c temp)))

(defn update-output [_] ;; <3>

(let [unit (get-input-unit)

input-temp (get-input-temp)

output-temp (convert unit input-temp)

output-label (target-label-for-input-unit unit)]

(set-output-temp output-temp)

(gdom/setTextContent output-unit-target output-label)))

- Extracted code for getting the converted unit label from the input unit

- Extracted code for converting a temperature from one unit to the other

- The impure code now only orchestrates the UI logic

Not only is the pure functional core of our code easier to test, it is also more resilient to changes that we may want to make to the UI and user experience application. If we wanted to change the way that the UI works, we would only need to replace the update-output function, not any of the conversion logic.

Referential Transparency

A function is said to be referentially transparent if it fits in the pure substitution model of evaluation that we have discussed. That is, a call to a function can always be replaced with the value to which it evaluates without having any other effect. This implies that the function does not rely on any state other than its parameters, and it does not mutate any external state. It also implies that whenever a function is called with the same input values, it always produces the same return value. However, since not every function can be referentially transparent in a real application, we apply the same strategy of keeping our business logic pure and referentially transparent while moving referentially opaque code to the “edges” of the application. A common need in many web apps is to take the current time into consideration for some computation. For instance, this code will generate a greeting appropriate to the time of day:

(defn get-time-of-day-greeting-impure []

(condp >= (.getHours (Date.))

11 "Good morning"

15 "Good day"

"Good evening"))

The problem with this code is that its output will change when given the same input (in this case, no input) depending on what time of day it is called. Getting the current time of day is intrinsically not referentially transparent, but we can use the technique that we applied earlier to separate side-effecting functions from a functionally pure core of business logic:

(defn get-current-hour [] ;; <1>

(.getHours (js/Date.)))

(defn get-time-of-day-greeting [hour] ;; <2>

(condp >= hour

11 "Good morning"

15 "Good day"

"Good evening"))

(get-time-of-day-greeting (get-current-hour))

;; "Good day"

- Factor out the function that is not referentially transparent

- Ensure that the output of our business logic is solely dependent on its formal parameters

This is a fairly trivial example, but any code that relies on external state - whether it is the time of day, the result of an API call, the (Math.random) random number generator, or anything other than its explicit parameters - breaks the functional paradigm and is more difficult to test and evolve as requirements change.

Immutable Data

We have just walked through the process of refactoring code that mutates the DOM into an impure wrapper around a functional core. However, there is another type of side effect that we must avoid if we want to write functional code: data mutation. In JavaScript, the two built-in collection data structures - objects and arrays - are mutable, meaning they can be modified in-place. All of the object-oriented features in JavaScript rely on mutability. For example, it is very common to see code that makes directly manipulates an object, such as the following:

const blog = {

title: 'Object-Oriented JavaScript',

tags: ['JavaScript', 'OOP'],

rating: 4

};

blog.tags.push('mutability');

blog.rating++;

blog.title += ' considered harmful';

blog.isChanged = true;

In ClojureScript, instead of modifying an object, we create copies of the original object with modifications. While this sounds inefficient, ClojureScript uses data structures that are constructed in such a way that similar objects can often share much of their structure in the same memory locations. As we will see, these immutable data structures actually enable highly-optimized user interfaces and can even speed up an application. Working with immutable data structures takes a mind shift but is every bit as easy as working with mutable data, as we can see below.

(def blog {:title "Functional ClojureScript"

:tags ["ClojureScript" "FP"]

:rating 4})

(def new-blog

(-> blog ;; <1>

(update-in [:tags] conj "immutability")

(update-in [:rating] inc)

(update-in [:title] #(str % " for fun and profit"))

(assoc :new? true)))

new-blog ;; <2>

; {:title "Functional ClojureScript for fun and profit",

; :tags ["ClojureScript" "FP" "immutability"], :rating 5, :new? true}

blog

; {:title "Functional ClojureScript", :tags ["ClojureScript" "FP"], :rating 4}

- Build up a series of transformations using the

->macro - Inspect both the original

blogand transformednew-blogmaps

In this example, we see that the original blog variable is untouched. We stack a series of modifications on top of the blog map and save the modified map as new-blog. The key takeaway here is that none of the update-in or assoc functions touched blog - they returned a new object that was similar to the one passed in but with some modification. Immutable data is key to functional programming because it gives us the assurance that our programs are repeatable and deterministic (at least the parts that need to be). When we allow data to be mutated as it is passed around, complexity skyrockets. When we allow mutable data, we need to keep track of a potentially enormous number of variables in our heads to debug a single computation.

NOTE

The author once worked on a team responsible for a very large JavaScript application. That team discovered that unexpected mutation was the cause of so many defects that they started keeping a tally of every hour spent finding and fixing bugs that were due to mutable data. The team switched to the Immutable.js library when their tallies no longer fit on the whiteboard.

Functional Design Patterns

Design patterns have gotten something of a bad reputation over the past decade or so, and in many cases, the criticism has been well-deserved. Most of the “Gang of Four”1 design patterns were discovered as workarounds for a lack of flexibility in the object-oriented languages at the time. In fact, Peter Norvig, a major player in the Lisp and AI communities, found that 16 out of the 23 design patterns presented in the Gang of Four book are either unnecessary in Lisp or arise through natural use of the language.2 Still, the goal of design patterns is to create a common vocabulary around describing problems that occur often in software development and present a template for an often-used solution. Even in a dynamic functional language like ClojureScript, there is some merit to defining problem and solution sets that occur often, so in this section, we will describe several: constructor, closure, strategy, and middleware.

Constructor

This should be a familiar pattern, as we already covered it in Lesson 19 and revisited it in Lesson 20. The idea here is to abstract the creation of some data structure behind a function in order to assign a name to that data structure and to make it easier to change the structure in the future. Since we have already been using this pattern for a couple of lessons, we need not belabor an explanation here.

Closure

Like JavaScript, ClojureScript has the concept of lexical closures. That is, a function can refer to any variables that were visible in the scope in which the function was defined. This allows us to retain (immutable) state in our functions. This allows us to do things like define a DOM element at the top level of a namespace and refer to it within a function defined in that same namespace:

(def user-notes (gdom/getElement "notes"))

(defn get-notes []

(.-value user-notes))

This is a pretty trivial use of a closure. Their real power shines when used in conjunction with higher-order functions. Recall how at the beginning of this chapter we defined an add function that simple adds 2 numbers together. We then used partial application to generate a function that always adds 5 to its argument. It would be much more flexible, however, if we defined a make-adder function that accepts a number and returns an adding function that always adds that number to its argument. Because of closures, we can do this:

(defn make-adder [x]

(fn [y]

(add x y)))

((make-adder 1) 5) ;; 6

((make-adder 2) 5) ;; 7

((make-adder 10) 5) ;; 15

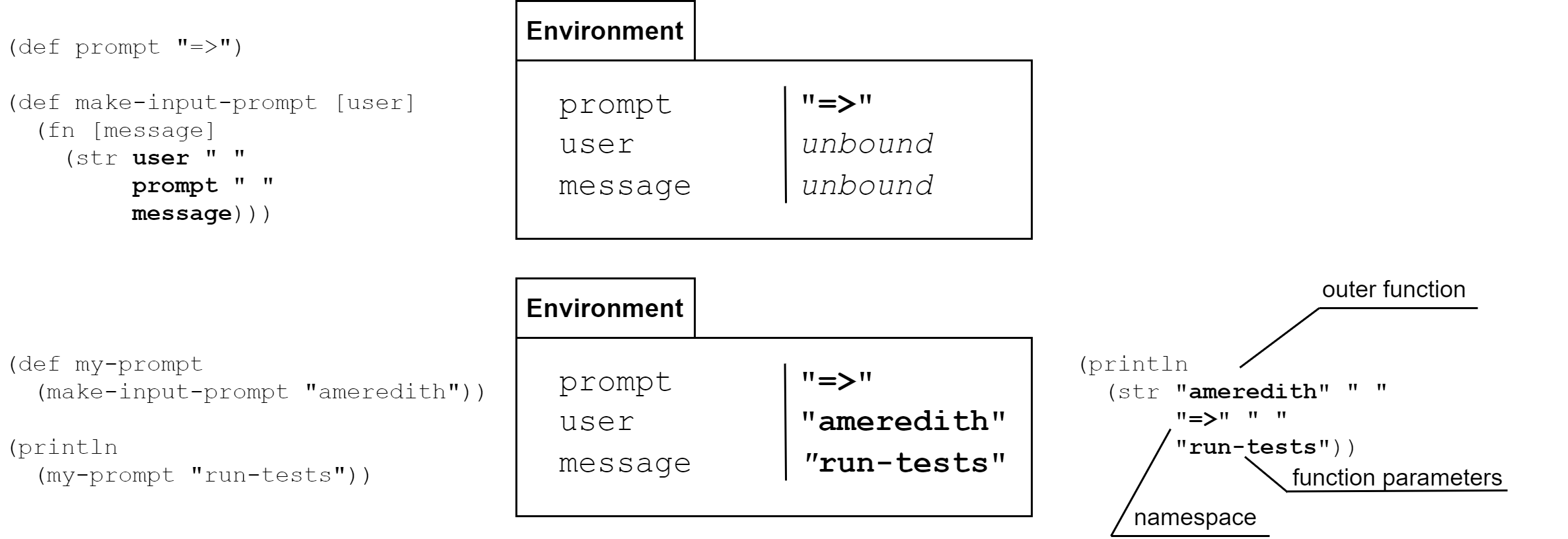

Note that the function we return from make-adder can reference any arguments passed into is parent function by name. Closures require us to tweak the mental model of evaluation that we introduced back in Lesson 4 and extended in Lesson 12, since we can no longer assume that we can simply replace a function call by the function’s definition with all formal parameters replaced by actual parameters. If we did that in the make-adder case, we would end up with the following:

((make-adder 1) 10)

((fn [y]

(add x y)) 10)

This would be a big problem because we would “lose” knowledge of the 1 that we passed into make-adder and would leave the symbol x that is not bound to any value. Let’s introduce the concept of an environment, which is simply a mapping of symbols to vars that were visible where the function was defined, and update our model of evaluation to say that when we evaluate a function, we replace all symbols within the function definition with the formal parameter of the same name or the value found for the corresponding name in the environment if no matching formal parameter is found.

Using this simple principle, we can use closures to emulate objects from the OOP world. Consider that we have a constructor that takes some initial state for an object, and we return a map of functions that can either update this state, returning a new object, or query the state, returning some value.

(defn make-mailbox

([] (make-mailbox {:messages [] ;; <1>

:next-id 1}))

([state]

{:deliver! ;; <2>

(fn [msg]

(make-mailbox

(-> state

(update :messages conj

(assoc msg :read? false

:id (:next-id state)))

(update :next-id inc))))

:next-unread ;; <3>

(fn []

(when-let [msg (->> (:messages state)

(filter (comp not :read?))

(first))]

(dissoc msg :read?)))

:read!

(fn [id]

(make-mailbox

(update state :messages

(fn [messages]

(map #(if (= id (:id %)) (assoc % :read? true) %)

messages)))))}))

(defn call [obj method & args]

(apply (get obj method) args)) ;; <4>

(defn test-mailbox []

(loop [mbox (-> (make-mailbox)

(call :deliver! {:subject "Objects are Cool"})

(call :deliver! {:subject "Closures Rule"}))]

(when-let [next-message (call mbox :next-unread)]

(println "Got message" next-message)

(recur

(call mbox :read! (:id next-message)))))

(println "Read all messages!"))

;; Got message {:subject "Objects are Cool", :id 1}

;; Got message {:subject "Closures Rule", :id 2}

;; Read all messages!

Purely Functional Objects

- Provide a no-arg constructor for convenience

- By convention, methods ending in

!will update the object state and return a new object - Methods not ending in

!will not update the object but will return a value instead applycalls a function with a collection of arguments

You Try It

- Add a few more methods to the mailbox “object”:

:all-messages- returns all messages in the mailbox:unread-messages- returns all unread messages in the mailbox:mark-all-read!- mutates the state by marking every message as read

Strategy

As in object-oriented programming, the strategy pattern is a way to separate the implementation of an algorithm from higher-level code. This pattern is so natural in functional languages that it barely qualifies as a pattern. Let’s take an example from the standard library: filter. This function filters (surprise, surprise!) a sequence, but it does not specify the criteria by which each element should be tested for inclusion. That criteria is dictated by the function passed to filter, which specifies the concrete strategy for determining which elements should be included in the new sequence.

(let [xs [0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]]

(println (filter even? xs))

(println (filter odd? xs)))

;; (0 2 4 6 8)

;; (1 3 5 7 9)

Middleware

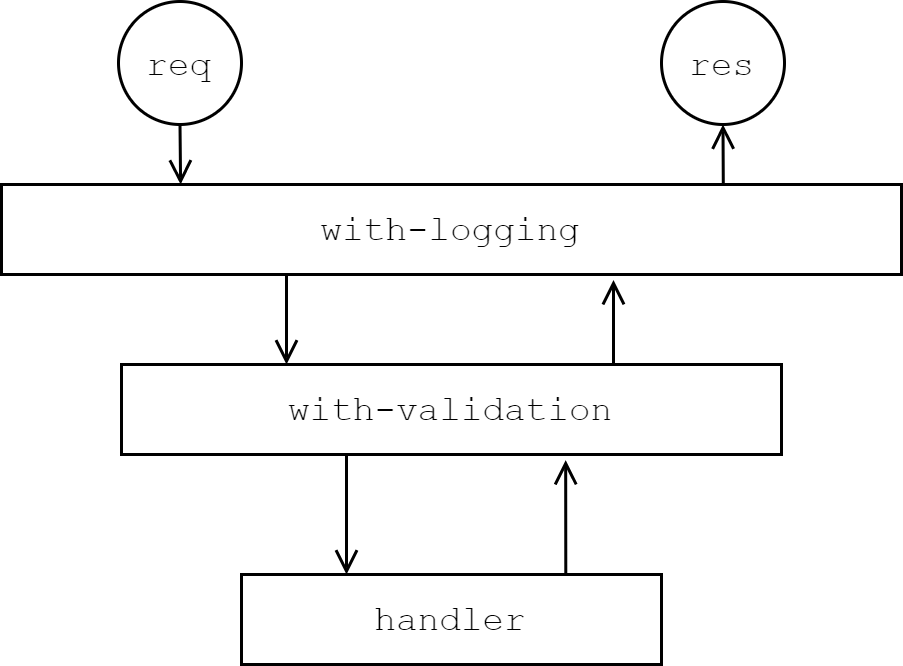

The final pattern that we will consider is the middleware pattern. This pattern allows us to declare “hooks” in a request/response cycle that can transform the request on the way in, the response on the way out, or both. It can even be used to short-circuit a request.

Imagine that we need to make a call to some API, but we want to be able to validate the request before it is sent. We could add the validation logic directly to the function that performs the API request, but this is less than ideal for two reasons: first, it couples validation logic to API logic, and second, it makes our app less testable by combining both pure and impure business logic in the same function. No problem, let’s add separate validation function:

(defn handler [req]

(println "Calling API with" req)

{:data "is fake"})

(defn validate-request [req]

(cond

(nil? (:id req)) {:error "id must be present"}

(nil? (:count req)) {:error "count must be present"}

(< (:count req) 1) {:error "count must be positive"}))

;; Client code

(if-let [validation-error (validate-request req)]

validation-error

(handler req))

This works well for a while, but now we need to add logging around each request that goes out and its response. We could add more logic to our client code, such as the following:

(do

(println "Request" req)

(let [res (if-let [validation-error (validate-request req)]

validation-error

(handler req))]

(println "Response" res)

res))

Even with 2 hooks that we want to add to the request/response, the code is starting to get unwieldy. With the middleware pattern, we can extract each hook into a function that “wraps” the handler function. A middleware is simply a function that takes a handler and returns a new handler. If we think of a handler in general as any function from Request -> Response, then a middleware is a function from (Request -> Response) -> (Request -> Response). One nice feature of middleware is that since they have the same input and output types, they can be combined in any order using ordinary function composition!

Middleware Pattern

Returning to the wrapped API handler example above, writing the validation and logging as middleware would look something like the following:

(defn with-validation [handler]

(fn [req]

(if-let [error (validate-request req)]

error

(handler req))))

(defn with-logging [handler]

(fn [req]

(println "Request" req)

(let [res (handler req)]

(println "Response" res)

res)))

(let [wrap-handler (comp with-logging with-validation)

handler (wrap-handler handler)]

; Example invalid request

(handler {})

;; Request {}

;; Response {:error id must be present}

; Example valid request

(handler {:id 123, :count 12})

;; Request {:id 123, :count 12}

;; Calling API with {:id 123, :count 12}

;; Response {:response is fake}

)

Quick Review

- Why can middleware be composed using ordinary function composition?

- Does the order in which middleware are composed matter? What would have happened if we defined

wrap-handleras(comp with-validation with-logging)?

Summary

In this lesson, we looked briefly at three cornerstones of functional programming: minimizing and segregating the side effects, using immutable data, and keeping our business logic referentially transparent. When we these ideas, we naturally write programs that take a piece of data, pass it through a number of transformations, and the result is the output of the program. In reality, most programs are made up of many pure data pipelines that are glued together with impure code that interacts with the DOM, but if we follow the functional programming concepts that we have learned in this lesson, we will end up with a clean functional core of business logic that is primarily concerned with data transformation. Over the next few lessons, we will learn more language features and techniques that will enable us to be effective practitioners of functional programming.

Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software by Erich Gamma, John Vlissides, Richard Helm, and Ralph Johnson ↩︎