Lesson 24: Handling Exceptions and Errors

We would like to think of programming as an idealized discipline where we write our programs declaratively and the computer converts them into pure computational models that can churn away until the heat death of the universe. In practice, bad things will happen, and they will happen much sooner than the heat death of the universe. Networks fail, we divide by zero, we miss a corner case that generates input in the “wrong” shape. All of these are exceptional conditions that we need to be aware of and somehow handle when they occur. Welcome to the domain of exceptions!

In this lesson:

- Handle exceptional conditions with try/catch

- Add metadata to errors

- Handle exceptions as values

- Use conditions for more flexible error handling

Handling Exceptions with try/catch

Handling exceptions in ClojureScript is more similar to than it is different from handling them in JavaScript. ClojureScript provides a special form called try that compiles down to a try/catch construct in JavaScript. The basic usage should look familiar to any JavaScript programmer:

(try

(do-stuff 42)

(call-api {:id 17}) ;; <1>

true ;; <2>

(catch js/Error e ;; <3>

(println "An error occurred:" e)

false)

(finally

(do-cleanup))) ;; <4>

- Multiple expressions can occur inside the body of

try tryis an expression and returns a valuecatchis always used with the class of the value that should be caught- If a

finallyclause is present, it is called for side effects

While try/catch behaves almost exactly like its JavaScript counterpart, there are a few differences that are worth noting:

First, try is an expression rather than a statement. When all of the expressions inside the body of the try succeed, then the try itself evaluates to the value of its body’s final expression. When any expression throws an exception that is caught, the try evaluates to the value of the final expression in the catch block. Just like in JavaScript, a finally clause may optionally be specified. If it is, it will be run purely for side effects after the body and potentially the catch clause are evaluated. Only the value of the body of the try (on success) or the body of the catch (on failure) will be returned - the value of finally is discarded.

Second, the constructor of the exception to catch must be specified, and if the value thrown is not of that constructor’s type ,the catch clause is not evaluated, causing the exception to be re-thrown. This requirement arises from ClojureScript’s roots in Clojure, which runs on the JVM and whose try/catch form mimics that of Java. In order to maintain more syntactic consistency with Clojure, ClojureScript follows the same syntax. In practice, js/Error is almost always used as the value of the error type. However, since JavaScript lets us throw any value - not just an Error - there are times when we need to catch some other value. In lieu of the constructor of the error, we may use the keyword :default to catch a value of any type - including ClojureScript values:

dev:cljs.user=> (try

#_=> (throw {:type :custom-error

#_=> :message "Something unpleasant occurred"})

#_=> (catch :default e

#_=> (println "Caught value:" e)))

Caught value: {:type :custom-error, :message Something unpleasant occurred}

nil

Quick Review

1. What is the value of each of the following expressions?

;; 1

(try

:success

(catch :default _

:failure))

;; 2

(* 2

(try

(throw (js/Error.))

4

(catch :default _

6)

(finally 8)))

;; 3

(try

(try

(throw "a string")

(catch js/Error e

"Inner")

(catch :default e

"Outer")))

Conveying Information

Sometimes it is desirable to convey extra information when we throw an error. For instance, if we are loading a string from localStorage, parsing it, then using it to construct a domain object, there are at 3 steps that can fail, and we probably want to handle these failures differently - perhaps to determine what type of message to display to the user or whether to log the error to a service for later inspection. In this case, we can use ex-info to create a ExceptionInfo object, which is a subclass of the JavaScript Error type that ClojureScript defines. This function allows us to attach a message, a map of arbitrary metadata, and an optional field describing the cause of the exception. For example:

(ex-info "A parse error occurred" ;; <1>

{:line 17 :char 8 :last-token "for"} ;; <2>

:unexpected-end-of-string) ;; <3>

Creating an ExceptionInfo error

- Error message

- Metadata

- Cause (optional)

When we catch an ExceptionInfo, we can use the ex-message, ex-data and ex-cause functions to extract the extra information back out. Going back to the example of parsing a string in localStorage and hydrating a domain model from it, we can detect the type of error and handle it differently depending on where the error occurred.

(def required-attrs [:id :email])

(def allowed-attrs [:id :email :first-name :last-name])

(defn make-user [user-data]

(cond

(not (every? #(contains? user-data %) required-attrs))

(throw (ex-info "Missing required attributes"

{:required required-attrs

:found (keys user-data)}

:validation-failed))

(not (every? #(some (set allowed-attrs) %) (keys user-data)))

(throw (ex-info "Found disallowed attributes"

{:allowed allowed-attrs

:found (keys user-data)}

:validation-failed))

:else (assoc user-data :type :user)))

(defn hydrate-user []

(let [serialized-user (try

(.getItem js/localStorage "current-user")

(catch js/Error _

(throw (ex-info "Could not load data from localStorage"

{}

:local-storage-unsupported))))

user-data (try

(.parse js/JSON serialized-user)

(catch js/Error _

(throw (ex-info "Could not parse user data"

{:string serialized-user}

:parse-failed))))]

(-> user-data

(js->clj :keywordize-keys true)

make-user)))

(try

(hydrate-user)

(catch ExceptionInfo e

(case (ex-cause e)

:local-storage-unsupported

(display-error (str "Local storage not supported: "

(ex-message e)))

:parse-failed

(do (display-error "Could not load user data from browser")

(log-error {:type :user-parse-failed

:source (:string (ex-data e))}))

:validation-failed

(do (display-error "There was an error in your submission. Please correct it before continuing.")

(update-field-errors (ex-data e)))

;; Re-throw an unknown error

(throw e))))

Using this pattern, we can provide more information along with an exception that can be used by the handling code in order to dispatch different business logic. In JavaScript, we can achieve a similar result by sub-classing Error and including instanceof checks in our error handling logic. ClojureScript is simply a bit more opinionated, and it provides the tools to do this out of the box.

Functional Alternatives to Exceptions

While handling errors with try/catch should be familiar to every JavaScript developer, it runs against the grain of pure functional programming, of which we have already seen the benefits. When exceptions can be thrown, a function is no longer a mapping of input to output. It additionally becomes a mechanism for signaling control flow: when a function throws an exception, it does not return a value to its caller, and the code that ultimately receives the value thrown is not necessarily the immediate caller. We can always use the pattern that we learned in Lesson 21 to segregate our exception-handling code from our core business logic. This is usually possible, and it is often the simplest option. However, there are more functional ways to handle exceptional conditions, and we will look at two of those: treating errors as values, and using condition systems.

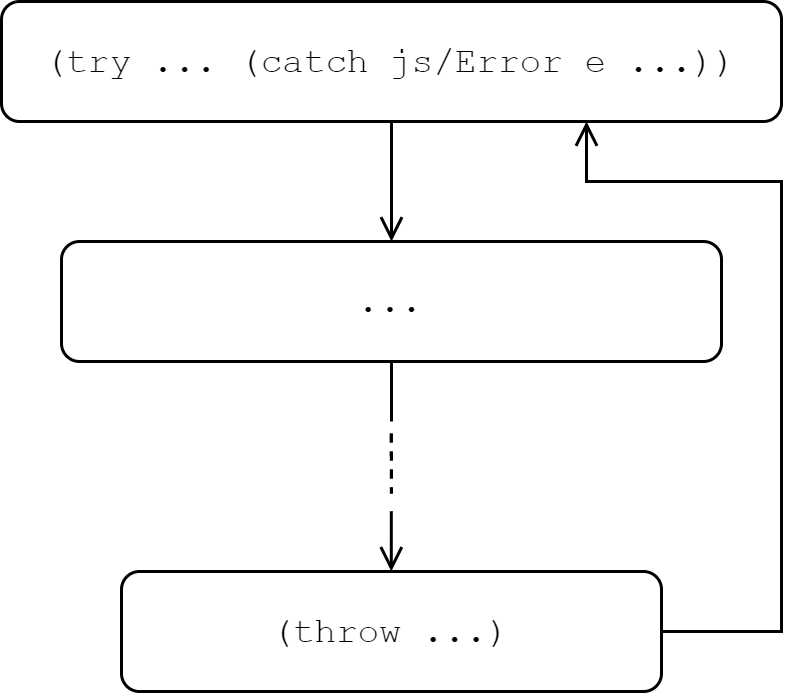

Control Flow for try/catch

Errors as Values

The simplest and most functionally pure option for writing code to deal with exceptional conditions is to simply return any error that may occur. In this case, a function that may fail will return a wrapper value that can contain either a success value or an error. There are many ways to represent a wrapper value, but a simple option is as a 2-element vector that either has :ok in the first position and a normal value in the second position or has :error in the first position and an error value in the second position. It is trivial to create a few functions that define this “error” type and work with its values:

(ns errors.err

(:refer-clojure :exclude [map]))

(defn ok [val]

[:ok val])

(defn error [val]

[:error val])

(defn is-ok? [err]

(= :ok (first err)))

(def is-error? (complement is-ok?))

(def unwrap second)

(defn unwrap-or [on-error err]

(if (is-ok? err)

(unwrap err)

(on-error (unwrap err))))

(defn map [f err]

(if (is-ok? err)

(-> err unwrap f ok)

err))

(defn flat-map [f err]

(if (is-ok? err)

(-> err unwrap f)

err))

Defining an error type

With these few functions, we can construct and transform values that have this “error type” wrapper.1

(defn div [x y] ;; <1>

(if (zero? y)

(error "Cannot divide by zero")

(ok (/ x y))))

(unwrap (div 27 9)) ;; <2>

(unwrap (div 27 0)) ;; <3>

(map #(+ % 12)

(div 27 9)) ;; <4>

(unwrap

(flat-map ;; <5>

#(div % 2)

(div 27 9)))

- Define a division function that can fail if asked to divide by

0 - A success value,

[:ok 3] - An error value,

[:error "Cannot divide by zero"] mapwill transform a success value inside an error typeflat-mapwill take a success value inside an error type and return the result of passing this to another error-type producing function.

When we write code in this style, we can end up with functions that all include the same boilerplate. For example, every function that handles an error returned by another function that it calls will look like the following:

(defn get-results-and-handle-error []

(unwrap-or

(fn [err] ;; <1>

(display-err err)

[])

(get-results))) ;; <2>

Handling an Error

- The callback will be called when

get-resultsfails, and its value will be returned fromget-results-and-handle-error get-resultsmay fail

On the other hand, when we have a function that should propagate an error when one of the functions that it calls fails, our function will look like this:

(defn transform-results-and-propagate-error []

(map

#(transform-results %) ;; <1>

(get-results)))

Propagating an Error

transform-resultswill be called with results only whenget-resultssucceeds

The downside to this approach is that we need always be mindful of which functions may fail and deal with their results as wrapped results. In the end, we have more boilerplate for handling errors, but our control flow is explicit, and our functions remain free of side effects. Sometimes the trade-off will be worthwhile, but other times we are better served by a judicious use of exception handling code at the boundaries of our application. There are several excellent libraries that help minimize the boilerplate associated with this error-as-value approach, such as Adam Bard’s failjure.

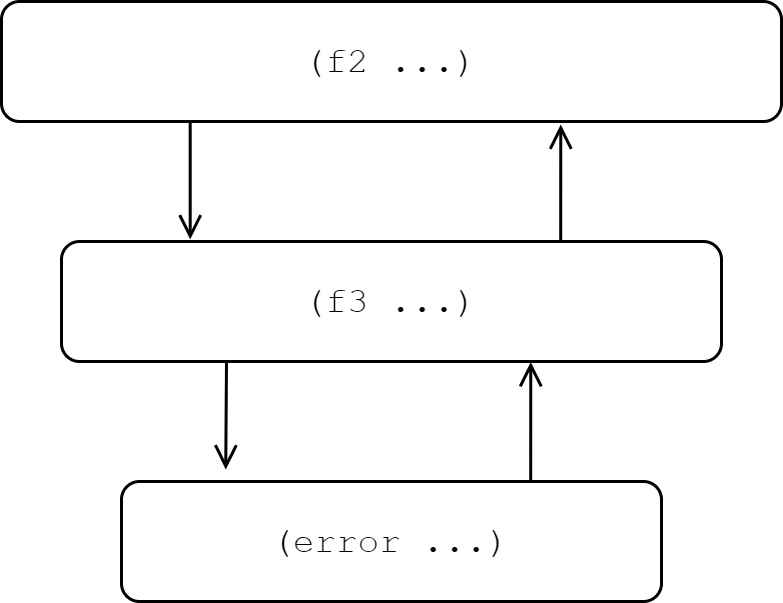

Control Flow for Errors as Values

Conditions and Restarts

Given the long history of the Lisp family of programming languages, we should briefly mention the concept of conditions, which were popularized in Common Lisp.2 The basic idea behind a condition system is that there are pieces of code that can have different outcomes that are beyond our control. For example, we cannot parse malformed input, a browser may have disabled a certain feature that we wish to use, etc. Additionally, the code that encounters these special conditions is not necessarily the code that we want deciding what to do as a result. However, control should not be passed arbitrarily far up the call stack when some condition is encountered. A popular library for working with conditions in ClojureScript is special.

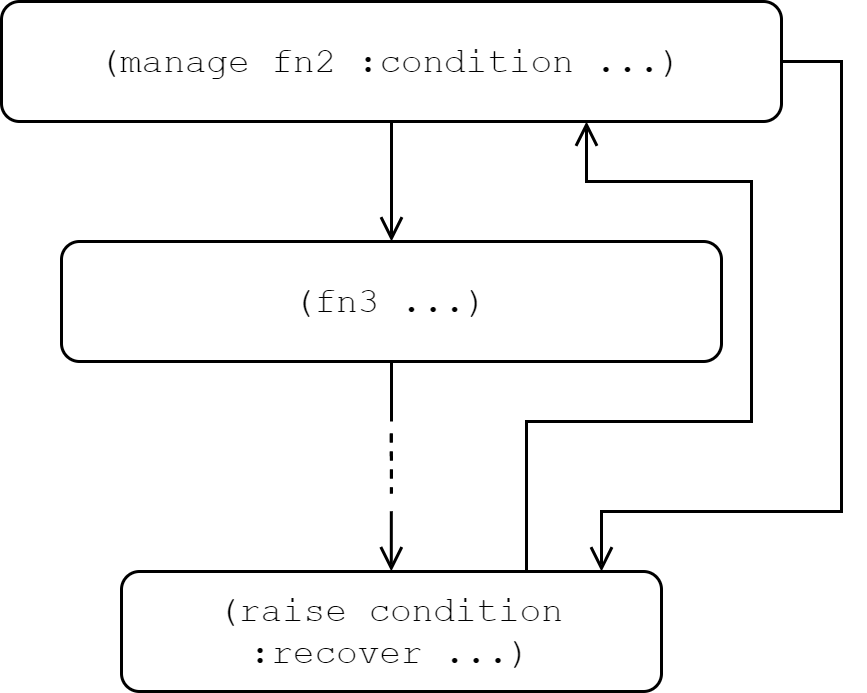

Condition systems let us signal a condition, which may be handled by a function that was registered to handle that specific type of condition. Finally, this handler can optionally invoke a restart, which returns control to the location where the condition was signaled. Additionally, the lower-level function that signaled the condition may offer multiple restarts, and it is up to the handler to choose which restart to invoke.

In order to see how this works, let’s return to the example of parsing a string in localStorage to hydrate a domain model. We end up with low-level code that we call from higher-level code. That low-level code that gets data from localStorage should not be in charge of deciding what is the appropriate course of action - otherwise, it gets coupled to the higher-level logic of the program and is no longer reusable. Using the special library, our code might look like this:

(defn get-localstorage [key]

(try

(.getItem js/localStorage key)

(catch js/Error _

(condition :localstorage-unsupported nil)))) ;; <1>

(defn get-parsed-data [key]

(let [serialized (get-localstorage key)]

(try

(if-let [parsed (js->clj

(.parse js/JSON serialized)

:keywordize-keys true)]

parsed

(condition :no-data key

:normally {})) ;; <2>

(catch js/Error _

(condition :parse-error {:key key :string serialized}

:normally {}

:reparse #(get-parsed-data %)))))) ;; <3>

(defn handle-parse-error [{:keys [key]}]

(if (= key "current-user")

(condition :reparse "currUser") ;; <4>

(do (display-error "Cannot parse")

(initialize-user))))

(defn hydrate-user []

(let [managed-fn (manage get-parsed-data ;; <5>

:localstorage-unsupported (fn [_] ;; <6>

(display-error "Unsupported")

"{}")

:parse-error handle-parse-error)

:no-data (fn [_]

(initialize-user)))]

(managed-fn "current-user")))

Handling conditions

- Signal the

:localstorage-unsupportedcondition withnil - Provide a default value if the condition is not managed

- Provide a “restart” that allows us to proceed with specific behavior

- Trigger the

:reparserestart - Create a managed version of the

get-parsed-datafunction with handlers for each condition type - Declare a handler as the condition keyword followed by a function of the condition value to the desired value

This example is fairly dense, so let’s unpack it a bit. First, there are two functions that we use as part of the condition system: condition and manage. condition signals a condition of a specific type along with a value. For example, when there is an error parsing user data, we signal the condition of type :parse-error with the value, {:key key :string serialized}. manage creates a version of the function that provides handlers for each condition that may be signaled, whether in the function that was called directly or in any functions that it eventually calls arbitrarily deep in the call stack. The handlers are given the value of the signaled condition and may either return a value that is used at the location where the condition was signaled, or they can signal a new condition.

This second option is how “restarts” are accomplished: when we signal a condition, we can provide restart handlers as well. The :normally handler is called automatically if no handler is provided higher in the call stack. Any other restart can be selected by raising the corresponding restart condition in uor handler function. In the example above, we provide a :reparse restart that attempts to parse data from another key from localStorage. We signal this restart in the handle-parse-error function: (condition :reparse "currUser"). This ability to provide code in the lower-level functions that can be dispatched based on higher-level logic is what makes conditions so powerful.

Control Flow for Conditions

Quick Review

1. What is the result of the following code?

(let [f (fn [s]

(if (= 0 (mod (count s) 2))

(condition :even-length s

:normally "EVEN"

:shout (.toUpperCase s))

(str "You said: " s)))

managed (manage f

:even-length (fn [s]

(if (= "loud" s)

(condition :shout)

(str s "!"))))]

[(managed "test")

(managed "foo")

(managed "loud")])

As we can see, conditions let us decouple the code that specifies the recovery strategy from the code that decides what recovery strategy to invoke. Like exceptions, conditions are not purely functional because they introduce control flow outside of the normal return value of a function. However, since a restart returns control to the function where the error occurred, they are closer to the functional end of the spectrum than are exceptions.

Summary

In this lesson, we learned how to use ClojureScript’s version of try/catch to deal with exceptions that occur in our code or code that we call. We saw how to use ex-info to create error values that convey extra information that we can use in our error handling code. Finally, we looked at two ways to approach errors in a more functional programming-friendly way. We “wrapped” the return values of functions that could fail in a special error type, and we also used conditions to allow higher-level code to specify the strategy for handling an exceptional case in lower-level code.